Texts: Ezekiel 34:11-16, 20-24 + Psalm 95:1-7a + Ephesians 1:15-23 + Matthew 25:31-46

“What I think, is that this is hell,” is what my sister told me.

By this point, I’d already gone to seminary. So it occurred to me, in the moment, that my sister was articulating a very present eschatology. By this point, she’d been living with a dual-diagnosis of persistent mental illness and mild developmental delay for a few years. She’d experienced the primal wound of being abandoned by her birth mother, raised in a foster home for the first six years of her life, and then torn from the land of her birth by loving, well-intentioned people who, nevertheless, did not look like her, or speak her language. By this point, my sister, Tara, who is Thai by birth and gifted with beautiful, lustrous brown skin, had experienced a childhood filled with racism both ignorantly casual and pointedly vicious. She had spent years running away from home, running toward danger. She’d been exposed to the violence that comes with life on the streets. She’d been beaten, she’d been exploited, and when she turned to the police in a life-or-death moment looking for help escaping the horrors of her immediate surroundings, they’d taken one look at her and saw only a disheveled, disorganized, dirty, brown-skinned girl with a funny way of talking and they told her to get lost, as if she wasn’t already.

So we were talking, she and I, about resurrection, and what hope we may have for the future, for a life better than the ones we’d known. I was talking to her about the miracle of tulips, which seem to die over and over, only to break free from the earth again and again to show their beauty in their frailty. And that’s when she told me, “what I think, is that this is hell.”

So, my reflection on this passage from Matthew has to start there, in hell, though the text itself does not use that word. This scene of final judgment, which is unique to Matthew’s gospel, is “the only scene with any details picturing the last judgment in the New Testament.”[1] Here we hear Jesus speaking in the voice of the ruler of heaven and earth seated on a cosmic throne before all the nations, rendering a judgment that addresses each person, each of us, on the basis of how we have responded to the human beings in our midst who are experiencing on a daily basis the depth of the hells this world has to offer: hunger, thirst, hostility to all that is strange or foreign or different, the bare naked exposure of poverty, the wretchedness of disease and illness, the graceless confines of our retributive justice and our merciless prison industrial complexes. In this scene of final judgement, the Lord of the universe says nothing about people’s personal sentiments, or public proclamations. The Lord gives no consideration to who you have claimed as your “personal Lord and savior.” The Lord of time focuses, like my sister, on the present and the fires to which we have consigned each other and asks what we have done for those whose daily reality is a burning hell.

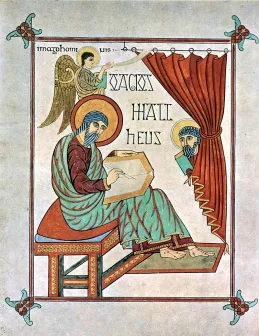

I haven’t always known quite what to do with the festival of the Reign of Christ at the end of each liturgical year. Over time, however, I’ve come to appreciate the opportunity it provides for us to consider the distinctive voice of the synoptic gospel assigned to the year now ending. For this last year, it has been the Gospel of Matthew. So we have been hearing the good news of the revelation of God in Jesus Christ in a recognizably Matthean mode. Matthew’s theological world draws us into a recognition of the reign of God in clear opposition to the reign of Satan; it is the only gospel to speak explicitly of the “church” as a description for the community of believers, and so it invites us to give consideration to what we think the church is and who is part of it; it insists that Jesus is the fulfillment of the law, not the abolishment of it, and in doing so it ties the ethical life of those who follow Jesus to the ethical demands of the prophets of Israel. Then there is the thorny matter of Matthew’s relationship to the rest of Judaism, as this gospel preserves the memory of a religious community divided within itself over the nature of the covenant, the revelation of the messiah, and the imperative of the present moment to acknowledge and respond to what God is doing now in human history.

These themes and tensions are always with us, and I was reminded of that fact as I read and re-read the Boston Declaration, a theological statement released last Monday at the annual meetings of the American Academy of Religion and the Society of Biblical Literature that publicly calls out American Evangelicalism for the ways that it has stoked the fires of a very real and present hell for millions of “the least of these” who suffer under the tyranny of intersecting ideologies of oppression that have interlaced racism, colonialism, and environmental degradation in ways that have created a living hell for the peoples of Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, and the US territories; that have privileged and prioritized profits for gun manufacturers over the lives of human beings; that have supported the violent hetero-patriarchy evident in the daily revelations of rampant sexual misconduct and abuse by men against women and girls in workplaces and in homes; that has scapegoated Jewish people, Muslim people, Black and Brown people, and Queer people for the sins of White Christian Patriarchy; for elevating the economic appetites of nations by respecting national borders more than the lives of those who cross them as immigrants or refugees from the living hells created by those very same nations.

The stark and unapologetically divisive nature of the Boston Declaration very much reminds me of the stark and unapologetically divisive nature of this scene from Matthew of the final judgment in which all the nations are gathered before God and the people are surprised once more to hear that God takes sides. That our apathy and misconduct cannot be dismissed or justified by our claims to ethnic or national or religious exceptionalism.

We all recoil from this scene, or should if we are in the least bit self-aware. The on-going presence of hunger and thirst, violence and poverty, malicious neglect of the ill and obscene incarceration of our neighbors who are, in fact, our siblings, indicts us all as complicit in the dominion of “the devil and his angels.” (Mt. 25:41) And it simply will not do to dismiss our discomfort with reminders of our Lutheran doctrine of justification by grace through faith; to let ourselves off the hook with reminders of God’s unceasing mercy, because it is God who addresses us here. It is God who speaks these words of judgment.

So we are left to grapple with the purpose and function of this eschatological vision and the tensions it produces. It is a tension that brings me back to my sister’s own declaration: “What I think, is that this is hell.” A very present eschatology, not unlike, I think, Jesus’s own eschatology. After all, it is in Matthew’s gospel that Jesus begins his public ministry by proclaiming, “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven has come near.” (Mt. 4:17) This is Matthew’s Christology, that Jesus brings the reign of God, the fulfillment of God’s promises in the past, into the present moment with consequences for all of human life, for all of creation, here and now. Now is the moment of judgment. Now is the assurance that God does, in fact, take sides. Now is the promise that the hells in which we are burning cannot stand against the waters of the Christ into whom we are baptized. Now is the moment of our salvation. Now, not in the words we say or the identities we claim, but in the acts of lovingkindness we perform for one another, for the needless misery we relieve, for the welcome we offer, for the liberation we effect. Now. Now. Now.

Hell is not a threat of future punishment by our God. It is now. Or at least that’s what I heard when I listened to my sister, one of the least of these, and I believe her. What do you suppose might happen if you, if all of us, believed the voices of the women and girls, of the strangers and foreigners, of the masses that are incarcerated, of the legions of the sick and dying, of those who hunger and thirst?

A final word before I say goodbye to Matthew for a couple more years:

We struggle with the vitriol Matthew voices against those he calls “the Jews” because of the long history of Christian anti-Semitism, which the Boston Declaration rightly both laments and condemns. In its own context, however, what Matthew gives witness to is an intra-religious conflict among people who understood themselves as belonging to the same faith, yet who still drew very different conclusions about what God was doing in the present moment and what their faith required of them as a result. Here, again, the Boston Declaration provides a timely example. We might wonder what this present moment will look like two thousand years from now to those who have the advantage of that perspective, who will be able to look back and see what this one group called Mainline Protestants said about another group called American Evangelicals. We cannot know how these divides will deepen, or heal. Perhaps we will continue to drift away from one another to such an extent that we can no longer even recognize ourselves as belonging to the same religion.

Here Matthew shows us the righteousness of God, in that, no matter how much Matthew the evangelist might wish to claim superiority over the other sects of Judaism on the basis of his theological declarations, in the end God once again confounds our ideas of righteousness by disrupting the borders we draw around nations, tribes, religions, identities by lifting up those who do what is needed to meet the needs of the wounded neighbor, the suffering sibling.

We, too, should hear this word: that God cares less for our Boston Declarations than for our actual presence with those who suffer. God cares less about the accuracy of our theological ideas than the impact of our public witness. Just as fifty years of dialogue with the Roman Catholic church has led us to a new commitment to shared acts of proclamation and service, we might imagine and should already be looking for ways to heal the rifts that divide us from the very people we now condemn. For surely, in the moment of judgment that is always already happening, we will discover once again that we are all a part of the same family, that we all bear Christ to one another, that we are all standing before the throne of God, and that we are all in this together.

Amen.

[1] “The Gospel of Matthew: Introduction, Commentary, and Reflections,” by M. Eugene Boring in The New Interpreter’s Bible, v.8, p.455 (1995: Abingdon Press)