This sermon was preached in Augustana Chapel at the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago (LSTC) on Monday, September 25th.

Texts: Jonah 3:10 — 4:11 + Psalm 145:1-8 + Matthew 20:1-16

In my own personal history of interpretation, this parable of Jesus has gone through a series of evolutions — each one raising different questions, none fully exhausting the possibilities of the story, which I suspect is an intentional teaching strategy on Jesus’ part.

As a confirmand, this story was presented to me as a parable of grace. The workers clearly perform different amounts of labor, yet are rewarded equally. I was nine years old when I got my first paper route to earn money toward the plane ticket that would take me to Thailand with my parents when we adopted my sister. As soon as I was legally able, at age fourteen, I got a part-time job at McDonald’s after school and on the weekends, so that I’d have some spending money to keep up with the consumer demands placed on young people who want to fit in with their peers. Early on, I’d accepted the social contract that my time was a commodity to be bought and sold on the labor market. As such, the wage slave in me knew that this story was, somehow, unfair. People who work more hours should get more pay.

As a confirmand, this story was presented to me as a parable of grace. The workers clearly perform different amounts of labor, yet are rewarded equally. I was nine years old when I got my first paper route to earn money toward the plane ticket that would take me to Thailand with my parents when we adopted my sister. As soon as I was legally able, at age fourteen, I got a part-time job at McDonald’s after school and on the weekends, so that I’d have some spending money to keep up with the consumer demands placed on young people who want to fit in with their peers. Early on, I’d accepted the social contract that my time was a commodity to be bought and sold on the labor market. As such, the wage slave in me knew that this story was, somehow, unfair. People who work more hours should get more pay.

But, I was taught, grace is not for sale and cannot be earned — and this is a story about grace. So the hard working student in me set his mind to mastering this bit of Lutheran dogma — there is nothing I can say or do to earn God’s grace, love, or forgiveness. God, like the owner of the vineyard, is free to do as God wishes. And what God wishes is for everyone to live upon the earth equally.

Later on, after college, I spent a year teaching junior high in the Boston Public School system. I learned a lot that year about the art of teaching, stuff I’d read in books about developmental psychology took on three dimensions in the young people with whom I spent my days. As I struggled to scale the undergraduate education of which I was so proud down to an age-appropriate takeaway for the twelve to fourteen year olds before me, I began to wonder what had been stripped out of my own Christian education and formation.

Like this parable. Was God really like the owner of the McDonald’s franchise down the street from my folks’ house in Des Moines? Was the only thing being critiqued in this story the sense of injustice felt by the workers when the value of their labor was set aside for some kind of non-negotiated guaranteed income? I’d had just enough exposure to both Marx and post-modernism in college to be suspicious of this (and every) text. I wanted better answers to my questions.

In seminary I learned to read scripture with an awareness of the history surrounding each text, to ask questions about how power and wealth operated in the lives of the people who would have heard these stories first so that I could make better guesses about what these stories might have sounded like to their ears. I began to learn how military occupation had transformed a subsistence economy into an export economy, how ancestral lands had been stolen by invading powers, how peoples who’d once worked the land or fished the sea to feed their families now worked the land and fished the sea to earn a wage off of which their families could barely survive. I wondered why Jesus would tell such people a story about a land owner who took away their last inalienable asset, their labor, and would identify God with such an actor. God as the conquering power, the robber baron, the proto-industrialist, the erratic capitalist. My childhood faith held firm, that God wishes for everyone to live upon the earth equally, but how this story conveyed that message was far less clear.

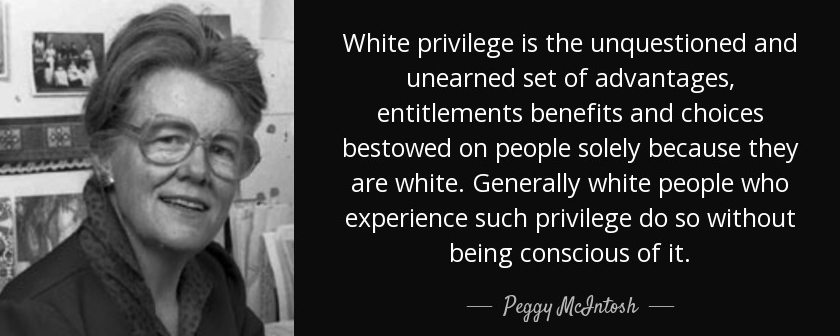

In 1989 Peggy McIntosh published the article, “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack,” giving fresh language and a new conceptual framework to an enduring problem. Twenty years later in 2009 she published a shorter, lesser known, article titled, “White People Facing Race: Uncovering the Myths that Keep Racism in Place.” In it, McIntosh asserts that white people “resist looking at racism because we fear damage to ourselves as ‘good people’ in the ‘greatest country’ in the world,” and asks the question, “how have whites kept such a strong sense of pride and deservedness?”

The answer she proposes is that white people have been raised on five strong cultural myths: meritocracy, manifest destiny, white racelessness, monoculture, and white moral elevation. It is the first of these myths, the myth of meritocracy, that draws my attention as I think about this strange parable of Jesus and wonder what he was doing when he told it to these occupied people in first century Palestine.

In her essay, McIntosh defines meritocracy as

“The myth that the individual is the only unit of society, and that whatever a person ends up with must be what [they] individually wanted, worked for, earned and deserved. This myth rests on the assumption that what people experience; how they see, feel, think, and behave; and what they are capable of accomplishing are not influenced by any social system or circumstance. The myth of meritocracy acknowledges no systems of oppression or privilege that, for various people and in various situations, could make life arbitrarily more, or less, difficult.”

When I look back and try to remember what nine year old Erik thought, as he delivered the newspaper; or what fourteen year old Erik thought, as he passed milkshakes through the window at the drive through, it’s complicated. There was some resentment, in that I realized that not everyone seemed to need to work in the ways I did to have the things I wanted. And there was some pride in discovering that when I worked hard, I could affect my environment. As a young person, who often had very little control over my environment, this was an empowering discovery. But I suspect it also laid the groundwork for a false logic that the powers of racism and capitalism later exploited: the assumption that everyone could just do what I did and get what I’d gotten. The myth of meritocracy.

I wonder if Jesus told this parable to people whose ancient ways of being and belonging were being disrupted as a way of agitating them, intentionally provoking them, helping them to remember that they had once been more than wage slaves and that in God’s economy they’d never been slaves at all. Could it be that this story wasn’t comparing God to a wealthy landowner, but instead critiquing the ways that both oppressor and oppressed come to accept and internalize the myths that structure and support all the violence that follows from them?

The myth of meritocracy is just that, a myth. It’s simply impossible that any of us is self-made. We are all products of the complex web of relationships that connects us to one another. For this reason, it’s just as impossible to say that any of us are getting what we deserve in any individual sense. Individually we are all simultaneously paying it forward and cashing in on the labor of others. It is only collectively that we might be able to say that we are reaping what we have sown.

Therefore, because we have sown fear of our neighbors, we have reaped this new travel ban. Because we have sown colonialism we have reaped devastation in the form of hurricane damage in Puerto Rico and throughout the Caribbean that could have been mitigated if the United States had invested in infrastructure and the economy long ago. Because we have sown white supremacy and enforced it with a militarized police force, we have reaped a national discourse in which taking a knee and proclaiming that Black Lives Matter is tantamount in the eyes of many to an act of treason. Here, the “we” I speak of stands in for all the various estate owners in my current understanding of this parable of Jesus; who are, most often, white people.

But our unpacking of this parable remains incomplete if we do not also ask ourselves how we have internalized the myth of meritocracy. How old were each of you when you learned the rules of this deadly game? When and how did you start playing by the rules? How has accepting the rules of this rigged game saved your life? How has it destroyed your relationships? What did you have to give up to get over?

I don’t think my confirmation teachers were lying to me when they bottom lined this parable as a story demonstrating that God’s love is free and cannot be earned. I just think they knew that we were only just beginning to understand the rules of the game, and that they themselves were caught up in the myth. I still believe, I know, that God wishes for everyone to live upon the earth equally. I also believe, I know, that Jesus will keep troubling my certainties and disrupting my attempts to accommodate myself to the lies this world tells, until we can all remember that we are all in this together.

Amen.

Hear this sermon preached aloud here.