Texts: Acts 17:22-31 + Psalm 66:8-20 + 1 Peter 3:13-22 + John 14:15-21

It’s Memorial Day weekend, as we all know, a national holiday originally established to honor the memory of those soldiers who died in the Civil War, but whose purpose has expanded over time to commemorate all Americans who have died while in military service. It’s also a holiday with a connection to our own neighborhood that some of you may know, but which was news to me as I was studying this week in preparation for this sermon.

There are many stories about how the Memorial Day holiday came to be a national holiday. One central figure in those stories is General John Logan, who was born in Jackson County, Illinois, fought in the Mexican-American War and the American Civil War and went on to serve in both the Illinois and the United States House of Representatives. Logan Square was named for him, and a statue of General Logan atop his horse stands in Grant Park just off East 9th Street.

According to legend, the idea for Memorial Day came from a pharmacist in New York who, in the summer of 1865 as the Civil War was drawing to a close, thought it would be a good idea for communities to remember those soldiers who would not be coming home from the war. He shared the idea with General John Murray, who, the following May, gathered the surviving veterans of Waterloo, New York to march to the local cemeteries where they decorated the graves of their fallen comrades. When General Murray later shared the story of this commemoration with General John Logan, he issued an order calling for a national observance.

A century later in 1966, as President Lyndon Johnson signed a presidential proclamation naming Waterloo, New York as the birthplace of Memorial Day, this is the story that was told. The reality, however, is that all kinds of similar observances were taking place in the north and in the south during and immediately after the end of the Civil War. All throughout the war, women gathered at the graves of fallen husbands and sons, decorating them so that their sacrifices would not be forgotten. The first widely publicized post-war public commemoration of those who’d died in the war took place in Charleston, South Carolina on May 1, 1865 at which nearly ten thousand people, most of them newly freed African Americans, gathered to lay flowers on the graves and to commemorate the lives of the hundreds of Union soldiers who had died there as prisoners of war. The event was reported on as far north as New York, where it appeared in the New York Times. Historian David Blight of Yale University writes,

“This was the first Memorial Day. African Americans invented Memorial Day in Charleston, South Carolina. What you have there is black Americans recently freed from slavery announcing to the world with their flowers, their feet, and their songs what the war had been about. What they basically were creating was the Independence Day of a Second American Revolution.” (Blight, David W., Lecture: “To Appomattox and Beyond,” oyc.yale.edu)

What seems most important to me is not who celebrated Memorial Day first, but the fact that it happened in so many places, on both sides of the line between north and south, and eventually in ways that honored the lives of all who’d died, whether they’d been defeated or were victorious in their cause. The human impulse was to gather together to remember their sacrifice, and to make meaning of it so that future generations would know how the world was made new.

Something similar is happening, I think, in the passages assigned for our worship this morning. Though these passages come from a series of readings that are used around the world and therefore take no notice of national holidays, they nevertheless also look back from the vantage point of the Easter resurrection to make sense of the power of a life given in service to God and God’s creation so that future generations would know how the world was made new.

In the Acts the Apostles Paul stands before a crowd of Gentiles in Athens, Greece and declares to them that the God of creation, the One who made heaven and earth, could not be bound to either their temples or their philosophies. He says, “The God who made the world and everything in it, [God] who is Lord of heaven and earth, does not live in shrines made by human hands” (Acts 17:24) and “we ought not think that [God] is like gold, or silver, or stone, an image formed by the art and imagination of mortals” (Acts 17:29). God is not a construct of masonry or the mind, so God cannot be tied to a temple or a theology. Instead, Paul says, “in [God] we live and move and have our being … for we too are [God’s] offspring” (Acts 17:28).

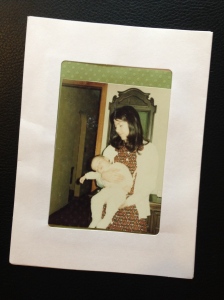

A couple of weeks ago my mom sent me a homemade card with a photograph she’d found in a drawer of her in her 20s holding me, probably just under one year old, completely relaxed and asleep in her arms. It’s a great picture, one that helps me to understand the point that Paul is making to the Athenians. As my mother’s offspring, what was most important was not the house we lived in, or my ideas about who she was, but the fact that I could rest in her arms knowing that I was completely safe and known and loved. That relationship, which began with an act of creation, predates my consciousness. I did not create that relationship, it created me. My relationship to my mother moved with me from one house to the next, even after I left her house to strike out on my own. My relationship to my mother grew as my ideas about her changed with each passing year, because relationships are dynamic and not fixed. My mother is not God, but resting in her arms in a moment before memory I was already learning something about how God holds me, and you, as we journey through our lives.

This, Paul tells the Athenians, is how God relates to each of us — through a living faith that survives the destruction of every temple, and the death of every idea. Knowing how in love we are with our ideas and our edifices, Paul says,

“God has overlooked the times of human ignorance, now [God] commands all people everywhere to repent, because [God] has fixed a day on which [God] will have the world judged in righteousness by a man whom [God] has appointed, and of this [God] has given assurance to all by raising him from the dead.” (Acts 17:30-31)

God has appointed a day, a Memorial Day of sorts, on which all people will come to understand the righteousness of God through the sacrifice of a life that changed the world.

Gathering decades after his death, the community of John’s gospel told the story of Jesus’ life and remembered that on the night before he died he told them “I will not leave you orphaned; I am coming to you” (John 14:18). By describing his coming death as act that will leave them feeling orphaned, Jesus takes on the role of their parent. In fact, in the verses just before these Jesus is sitting at the table of the last supper and the disciple whom he loved is described as resting on him. Artists have often depicted this disciple with his head on Jesus’ lap, the way I lay in my own mother’s arms, full of trust and love.

Gathering decades after his death, the community of John’s gospel told the story of Jesus’ life and remembered that on the night before he died he told them “I will not leave you orphaned; I am coming to you” (John 14:18). By describing his coming death as act that will leave them feeling orphaned, Jesus takes on the role of their parent. In fact, in the verses just before these Jesus is sitting at the table of the last supper and the disciple whom he loved is described as resting on him. Artists have often depicted this disciple with his head on Jesus’ lap, the way I lay in my own mother’s arms, full of trust and love.

This is the truth about grief that seems particularly useful to name today, as we commemorate Memorial Day. Whether we have lost our parents or our spouses or our children, whether we’ve lost close friends or professional colleagues, the experience of losing someone to death can stir up in us the memory of other losses or the fear of coming losses. Each death, in its own way, can feel like an act of abandonment as we, who are still living, lose the ability to see, and speak to, and touch the ones we’ve known and loved. We feel orphaned.

Speaking with the voice of a parent, Jesus not only promises not to leave his followers orphaned, he promises to ask the Father to send another Advocate to be with us forever. The imagery in these few verses is so rich that it will take us the next few weeks to sort through them all. The fact that Jesus describes the Advocate as the Spirit of truth anticipates the outpouring of the Holy Spirit which we will celebrate more fully on Pentecost in two weeks. The overlapping language of Jesus speaking as a parent, and to a parent, to send a spirit that will assure us all that we are in Christ, and Christ is in God and in us as well anticipates the festival of the Holy Trinity that follows immediately after Pentecost.

Remembering Paul’s admonishment that God will not be bound to our ideas about God, we can set aside our questions about these mysteries for the moment to focus on how God in Christ Jesus cares for those who are grieving, as many will be this weekend as they gather near the graves of loved ones who have died in our country’s on-going wars, or who remember other losses just as painful if less public.

Remembering Paul’s admonishment that God will not be bound to our ideas about God, we can set aside our questions about these mysteries for the moment to focus on how God in Christ Jesus cares for those who are grieving, as many will be this weekend as they gather near the graves of loved ones who have died in our country’s on-going wars, or who remember other losses just as painful if less public.

Jesus says that God will send another Advocate, to be with us forever. This provides at least two insights into how God cares for the grieving. The first part of this promise is that God will send another Advocate, which requires us to acknowledge that, in Jesus, God has already sent us an Advocate. This means that we have already seen how an advocate of God lives and moves and exists in the world. In Jesus we have seen how God heals the sick, feeds the hungry, gives hope to the poor, and organizes the people. In Jesus we have seen how God’s mercy and God’s justice are intertwined. The second part of this promise is that the next Advocate, which is the Spirit of truth, will be with us forever. This is only possible because the Holy Spirit, which is God’s promised Advocate, makes a home inside each one of us, which leads Jesus to say, “on that day you will know that I am in my Father, and you in me, and I in you” (John 14:20).

God cares for the grieving by giving us to one another. Ours are the ears that listen to the cries of the grieving. Ours are the hands that prepare the food dropped off at the home of those who mourn. Ours are the knees that kneel next to the grave. Ours are the arms that hold the child of God who cannot stand alone. Ours are the hearts that break open and refuse to stay hardened. Ours are the lives that testify to the God of creation, of all things seen and unseen, that look for the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come.

This Memorial Day, as we give thanks for the witness of so many who have given the last measure of their lives for the cause of freedom, we remember that the Advocate for our freedom and the freedom of every living person and all of creation is not dead, but is alive in us forever. Sent by the Spirit of truth to a broken, grieving world we offer the testimony of our lives so that future generations will know how the world was made new.

Amen.