Texts: 2 Kings 2:1-2,6-14 + Psalm 77:1-2,11-20 + Galatians 5:1,13-25 + Luke 9:51-62

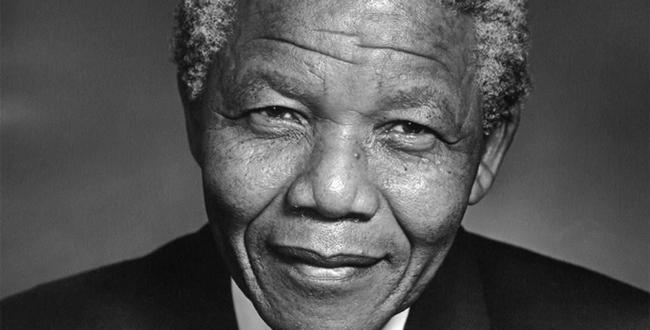

I’ve been keeping a close eye on the news, watching and waiting for any changes in the condition of the man President Obama has compared to George Washington, South Africa’s Nelson Mandela.

Mandela, as you know, became president of South Africa in 1994 after decades of struggling against the system of racial segregation known as apartheid. In his youth, Mandela was a lawyer involved in anti-colonial politics. He directly opposed the National Party that came into power in 1948, first non-violently, and later by leading bombing campaigns against military targets. He was captured, convicted of sabotage, and sentenced to life imprisonment, part of which was carried out on Robben Island, a prison compound off the coast of Cape Town.

Mandela served eighteen of his twenty-seven years of imprisonment on Robben Island, and the stories from that place are a part of his living legend: how he befriended the prison guards, reaching for their humanity in an inhumane place; how he gifted his captors with plants he grew on the windowsill of his tiny prison cell. I was in high school when the government of South Africa finally bowed to demands for his release, as he had grown to become an international symbol for the anti-apartheid movement. That was 1990. Four years later he’d gone from prison inmate to president of the newly reconstituted South Africa, an office he held from 1994 to 1999.

When I visited South Africa as a seminarian in the summer of 2000, Mandela’s presidency had just concluded, and the country was nervously making the transition from his leadership to that of his successor, President Thabo Mbeki. It was difficult to move from the iconic leadership of the man who had confronted the violent powers of the institutionalized racism of the Afrikaners’ National Party, and had lived to tell the tale, to his successor. There was a great deal of fear that the non-violent transfer of power from the National Party to the African National Congress, Mandela’s party, would finally break down and that the country would be plunged into violent conflict and civil war.

That was almost fifteen years ago, and South Africa has made the transition from one leader to the next more than once now, each time confirming Mandela’s vision for a peaceful, multicultural nation.

After leading the nation through decades of the anti-apartheid movement, then as its elected president for five years, in 1999 Nelson Mandela stepped down from public office, ready for a quiet family life. At the age of 80 he married his third wife, Graça Machel, also a political activist, from Mozambique. For the next few years he continued to be an active presence in South Africa’s political and cultural life. Then, in 2004, he announced that he was “retiring from retirement,” receding more fully from the public eye, though always in the national consciousness.

I asked Judith Kotzé, the South African LGBTI activist who was with us at the beginning of this month to share news and build support for IAM — Inclusive and Affirming Ministries — how South Africa was faring now that Mandela and Tutu, and other leaders of the anti-apartheid movement, were growing old and struggling publicly with their health. She said to me, “we are, of course, grateful for their leadership. They were symbols of the anti-apartheid movement. They brought the world’s attention to South Africa. But that was twenty years ago. Today we don’t need another Mandela, or another Tutu. We need networks of activists. We need the entire nation to push toward the vision they gave us.”

We’ve been traveling with the prophet Elijah through the book of First Kings for the last month, from his initial confrontations with King Ahab and Queen Jezebel, to his exile in the wilderness east of the River Jordan where he fed and healed the widow of Zarephath and her son. We remember how he condemned the power of the state when Naboth’s vineyard was illegally seized, and declared a coming day of judgment when the mighty would be brought low, and Israel would return to the Lord, its God. Last week we reflected on how lonely this work was, how silent God could be, how again and again those touched by God are sent back into the fray, when all they want is to be allowed to retreat from the struggle.

Finally, this morning we see Elijah retiring from his public ministry. He, alone among the prophets, does not die but is lifted into heaven by God whose power manifests in the appearance of a fiery chariot. Elijah is ready to make this journey, and even seems to prefer that he be allowed to take it alone, but his protégé and successor, Elisha, is determined to accompany him. Along the way from Gilgal to Bethel to the Jordan, Elijah and Elisha are joined by fifty others from a group we’ve not heard of before, called “the company of prophets.”

This company of prophets is one of the first signs we see that Elijah’s ministry has been about more than a dramatic public confrontation between power and the prophet. It has been about stirring the public’s imagination and creating a space in which people could begin to imagine themselves as members and leaders moving toward God’s vision for the world as it was meant to be.

In his book, Prophesy and Society in Ancient Israel, scholar Robert Wilson writes,

“Although there is no direct evidence on this point, members of [the company of prophets] were presumably individuals who had resisted the political and religious policies of the Ephraimite kings and who had therefore been forced out of the political and religious establishments. After having prophetic experiences these individuals joined the group, which was under the leadership of Elisha. In the group they found mutual support and were encouraged to use prophesy to bring about change in the social order.”

Reading between the lines of scripture the picture that emerges is that, far from his imagining, Elijah has not been alone in his struggle against empire. Inspired, perhaps, by his public witness, a community of prophets, a society of resisters, a network of activists has emerged who are already practicing the tools of prophesy, the art of truth-telling, to make change in the world around them.

This company of prophets, led by Elisha, accompany Elijah to the place of his ascension and there Elisha makes his request. “Please let me inherit a double share of your spirit.” Throughout his ministry, Elijah has performed miracles that confirmed his message. He created abundance where there was scarcity. He called down fire on his enemies, and commanded the waters to part before him. His message to the powers and principalities could not be ignored, when he was so obviously filled with power from another source. Elisha asks for that power, the power to lead with credibility and authority.

Elijah’s response to the eager young prophet is instructive. How often do we see leaders, whether it’s in business, or politics, or even the church, who try to select their successors. It is tempting, when a person has invested all of themselves into a lifelong project, to want to ensure that it will live on past the leader’s departure. How many companies, or movements, or congregations have suffered when a leader’s desire to select their successor saddles the community with the wrong person at the wrong time?

Elijah does not promise Elisha anything, because Elijah knows that his own ministry has been powered by his relationship to God. Elijah has argued with and complained to, but ultimately been faithful to the God who gave him power to meet the demands of the ministry to which he was called. Elijah knows that, in the end, it is God who will select his successor.

So he tells Elisha, “You have asked a hard thing; yet, if you see me as I am being taken from you, it will be granted you; if not, it will not.”

Here’s how I hear Elijah’s reply: if you have the vision, you will have the power. “If you see me as I am being taken from you…” If you can see that I was always about something greater than me, then you will still see me even when I myself am not here.

Elisha and the company of prophets had seen, and did know, that Elijah’s work had always been about more than Elijah. It had been about bringing the people of Israel back into right relationship with their God and with one another. It was a ministry that began during a drought, a sign that the king was not caring for the window, the orphan and the stranger, but which brought the rain. Over and against imperial power that sought its own interests at everyone else’s expense, Elijah’s ministry had been marked by costly truth-telling for the sake of the common good. Elisha, too, was marked as one ready to lead the twelve tribes of Israel; one who shares the vision for the world as God made it to be.

The story of a wonder-working prophet ascending into heaven, and leaving behind a community of followers ready to continue his ministry should sound familiar to any of us who have been Christian long enough to celebrate the festivals of Easter and Pentecost at least once. The gospel of Luke draws heavily on the story of Elijah in its presentation of Jesus. The people even wonder if Jesus is, in fact, Elijah returning for them.

They can wonder this, in part, because rather than dying, Elijah is taken up into heaven to be with God. This ending is powerful not because of the prestige it confers on Elijah, but because it defies resolution. Elijah is not dead, but ascended, which means that he might return at any moment. Indeed, the way Christians order the Hebrew scriptures, the last book of the Old Testament is Malachi, from which we read, “Lo, I will send you the prophet Elijah before the great and terrible day of the Lord comes.” (Mal. 4:5). To this day, our Jewish brothers and sisters leave a place at the Passover table for Elijah, who may yet come knocking at the door during the festival of liberation from the slavery of Egypt.

Likewise, we who are Christian, see in the stories of Elijah and Jesus a vision for God’s work in the world that is greater than any one person, a message that is bigger than the messenger. From Jesus’ own defiance against the slavery of the grave, we draw power and conviction that God’s work in this hurting, broken world is not done yet either. We have ordered the books of the New Testament so that they also end with the promise that God’s visionary Word will come again, as the book of Revelation ends with these words, “‘Surely I am coming soon.’ Amen. Come, Lord Jesus!” (Rev. 22:20)

And, of course, we say these words each time with gather for a meal at this table, as we recite the mystery of faith: “Christ has died. Christ has risen. Christ will come again.” And, “Amen! Come, Lord Jesus.”

These words, spoken over and over, aren’t magic spells that turn bread into sacrament, they aren’t ingredients in a liturgical recipe. They are pledges of allegiance to a new world order, the one we saw breaking in through Elijah, through Elisha and the company of prophets; through Jesus and the company of the apostles; through our brothers Nelson Mandela and Desmond Tutu. These words, “Amen. Come, Lord Jesus!” are acts of sedition, drawing us into a struggle for the future of the world.

Nelson Mandela was not released from 27 years of imprisonment so that he could enjoy his retirement. Nelson Mandela was set free in order to lead the people of South Africa, and the entire world, into a greater freedom. For freedom he was set free!

And so are you. So are you, my dear brothers and sisters, who by baptism have been initiated into the company of prophets, the community that looks at Elijah, and Jesus, and sees the message in the messenger. Who see the vision. Who are called prophets of the Most High.

You have not been set free from lives of bondage to racism, or classism, or sexism, or nationalism, or heterosexism, or militarism, or consumerism, or capitalism simply in order that you might enjoy a more peaceful life. In Christ, you have been set free from all these powers, powers that try to tell you who you are, powers that try to reduce you to one aspect of your identity, in order to liberate the world from these same lying, death-dealing powers.

After years of prophetic leadership that saw an end to apartheid, Nelson Mandela stepped back so that others, many others, could continue to work of freedom, truth-telling and reconciliation in South Africa. After a prophetic ministry that brought King Ahab and Jezebel low, that brought waters back to parched lands, Elijah withdrew so that others, a company of prophets, could lead Israel back to God. After a public ministry so encompassing of God’s politics that it led to a cross, a tomb, and a resurrection, Jesus sent the Holy Spirit so that we, together, the church, might become God’s advocates for God’s emerging reign of peace with justice, of a world of plenty shared equitably with all, of love for everyone forever.

We are called to be prophets of this reality. Whether we are working to relieve hunger, marching for LGBTQ equality and civil rights, working for passage of common sense immigration reform, organizing to ensure all citizens continue to enjoy equal voting rights. Whatever our vocation, whatever our cause, we are called to set our minds on freedom, this morning and every morning. Come, Lord Jesus!

Amen.

One thought on “Sermon: Sunday, June 30, 2013: Sixth Sunday after Pentecost”