Text: Acts 8:26-40

I spent the summer after my first year of seminary doing street outreach with runaway, homeless, and street-dependent youth in Atlanta in neighborhoods like Little Five Points, Midtown, the Old Fourth Ward, and downtown; but this phone call that I got on my very first cell phone (a flip phone) from an anxious mother didn’t come until the summer was over and I was back in school the fall of my middler year. I was walking back to my car after a morning of classes when the phone rang. Those were the days when I still picked up for unknown numbers. I answered expecting it to be someone from school, instead it was a woman who immediately asked who I was.

I told her my name, Erik, and wondered if she might have the wrong number. She said she’d gotten this number off a business card she found in her son’s bedroom. The card had my name and phone number and the name of my summer project, “Street Chaplains.” She wanted to know what it meant, street chaplain, and what I’d been speaking to her son about. I wish I could have taken a page from the recently terminated Congressional chaplain and replied, “hospital chaplains pray about health. Congressional chaplains pray about Congress. Street chaplains pray about the streets.”

But, the truth was, I had no idea what I’d said to her son. I’d spoken to hundreds of people over the course of the summer. I’d trained a handful of my classmates in the basics of safe, ethical outreach, work I’d done before going to seminary. Together we’d gone out in pairs, day after hot summer day, talking to every young person we found. We’d ask them if they had a safe place to sleep, or if they knew someone who didn’t. We handed out these business cards dozens of times every hour, and every once in a while we got to have a meaningful conversation with a young person experiencing homelessness. I didn’t always get people’s names, and I rarely remembered the ones I did get. So I really had no way of connecting this caller with a memory of her child.

The easier thing to do would have been to explain all this quickly and get off the phone. The summer was over, after all. The project was finished, the final report written and turned in. The subject of this conversation was in my past. To reopen the topic would be to make space for a detour on my way to the day I’d planned for myself. Except this woman had my number, and I still had the phone and this call.

I could hear something in her voice, a question she wanted to ask and an answer she didn’t want to hear. So I asked if her child was alright. She said, “I think he’s gay,” and I could tell from her voice that this thought brought her no joy.

I remember wondering what my duty was in that moment. Did she deserve to know that she was speaking to a gay man? Should I make that clear so that she could decide how much she wanted to say, or not to say? But I didn’t. Instead I told her that I’d met lots of LGBTQIA+ (well, I probably said “gay and lesbian”) kids out on the streets, kids who’d run away from home or been kicked out. Youth who’d been humiliated. Youth who’d been denied justice. Youth led to the slaughter. I didn’t say that last part, that’s from the scroll of the prophet Isaiah. And, because the business card said “chaplain” on it, she felt free to ask me; more than that, she wanted to know what I thought the bible had to say on the topic of gay and lesbian people (though I’m sure she said “homosexuals”). So, like Philip, I was invited to help interpret scripture.

I do remember one of the people I met that summer. I’d been outreaching in the Little Five points neighborhood on a scorching hot day. I was wearing cargo shorts, a baby blue short-sleeved clerical shirt and collar, and carrying an over the shoulder bag in which I’d packed business cards, bottles of water, a social services referral guide, condoms, etc. and I’d just purchased a soft serve ice cream cone to cool me down. Then I spotted this boy, almost a young man, no more than seventeen. He was tall, thin, white, all angles. I made it a practice to talk to anyone who looked twenty or younger, but he’d seen me scoping him out and he spoke first. Spinning on his heel to confront me at a stoplight that had just turned red, he unleashed the kind of fierce fury that’s hard for anyone over twenty to sustain. He came at me hard.

I do remember one of the people I met that summer. I’d been outreaching in the Little Five points neighborhood on a scorching hot day. I was wearing cargo shorts, a baby blue short-sleeved clerical shirt and collar, and carrying an over the shoulder bag in which I’d packed business cards, bottles of water, a social services referral guide, condoms, etc. and I’d just purchased a soft serve ice cream cone to cool me down. Then I spotted this boy, almost a young man, no more than seventeen. He was tall, thin, white, all angles. I made it a practice to talk to anyone who looked twenty or younger, but he’d seen me scoping him out and he spoke first. Spinning on his heel to confront me at a stoplight that had just turned red, he unleashed the kind of fierce fury that’s hard for anyone over twenty to sustain. He came at me hard.

“What are you looking at, preacher man?” I told him my name, explained what I was doing, and asked if he had a safe place to sleep. “People like you are the reason I don’t. ‘Hate the sin, love the sinner.’ That’s what the priest told my parents. So Dad showed me ‘tough love’ by kicking me out and telling me not to come home until I’d manned up. So excuse me if I don’t give a shit.” By now the ice cream had melted and was dripping down over my fist, but I couldn’t find anything useful to say. The boy just kept going, delivering his final blow, “Is your church ready for this homosexual?” My next words were pathetic and inadequate to the wounds this child had just revealed. I’ve never forgotten him, or his question.

As for this mother waiting on the phone for me to speak, I honestly don’t remember what I said next. I just know that the passages I might have quoted and the interpretations I would have given were not what she was expecting. I likely told the story from Acts 10 in which Cornelius calls for Peter, who then has the vision of the sheet being lowered from heaven, filled with unclean animals, and the divine voice that challenges Peter’s received theology and established practice, saying “What God has called clean, you must not call profane.” (Acts 10:15) Or maybe I quoted Romans 8:38, “For I am convinced that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor rulers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord.”

We spoke for fifteen minutes, twenty at the most. When it was over, she didn’t ask to meet me or request to be baptized. I wouldn’t even say she left the conversation rejoicing over the good news I’d shared. All I know is that, like Philip and the Ethiopian eunuch, I never heard from her again.

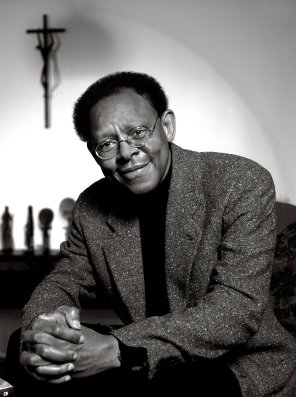

In the book of Acts, the Samaritan mission (under the leadership of Philip, whose saint day is observed tomorrow) signals the beginning of the spread of the gospel beyond the boundaries of traditional Judaism. For that reason, this story has served as an entry point for a number of communities that have historically been marginalized by the kinds of Christianity practiced by the dominant culture. When the Rev. Dr. Otis Moss came here to preach last fall, to kick off our commemoration of the 500th anniversary of the Reformation, this was the passage he selected for preaching, reminding us that this African figure has been misrepresented and aspects of his history and identity erased down through the centuries; the presumption that he was an outsider on the basis of his African identity a willful forgetfulness that Israelite religion had made its way to Africa as far back as King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba and that this Ethiopian eunuch is not identified in the text as a Gentile God-fearer, but simply as one “who had come to Jerusalem to worship.” He could just as easily have been a Jew attempting to worship at the temple. The very fact that later audiences, that White audiences, felt the need to imagine him as an outsider on the basis of his national identity, with its roots in Africa, speaks to modern racial ideas and not the worldview of the scripture itself.

This morning I can’t help but think that these insights owe a great debt to one of the most powerful theological voices of our generation, who died over the weekend. The Rev. Dr. James Cone, author of books that shaped a generation of teachers and leaders in the church and in society: Black Theology and Black Power, God of the Oppressed, The Cross and the Lynching Tree; teacher and mentor and guide. A man whose work reflected a holy anger at the disenfranchisement of black lives and disfigurement of black bodies, but will also be remembered for the warmth of his smile and the joy in his laughter. A fully human being, who we can imagine might have heard the desperation in the Ethiopian eunuch’s voice when he read aloud, “Like a sheep he was led to the slaughter, and like a lamb silent before its shearer, so he does not open his mouth. In his humiliation justice was denied him. Who can describe his generation? For his life is taken away from the earth” and then asked, “About whom, may I ask you, does the prophet say this, about himself or about someone else?” Because, at this point in the story, the Ethiopian eunuch does not know about Jesus, so we can only assume that he hears something in this account from Isaiah that reminds him of his own suffering, which reminds us of our own suffering, which is why this figure has remained central to the theological imaginations of all who suffer and therefore to liberation theology as well. I imagine Dr. Cone stepping into that chariot with Philip and the eunuch and teaching us once again that,

Either God is identified with the oppressed to the point that their experience becomes God’s experience, or God is a God of racism … The blackness of God means that God has made the oppressed condition God’s own condition. This is the essence of the biblical revelation. By electing Israelite slaves as the people of God and by becoming the Oppressed One in Jesus Christ, the human race is made to understand that God is known where human beings experience humiliation and suffering … Liberation is not an afterthought, but the very essence of divine activity. (A Black Theology of Liberation, pp. 63-64)

What lesbian and gay, bi and trans, queer and intersex, non-binary folk and anyone else whose sexual or gender identity is not normalized by culture have seen in the Ethiopian eunuch is one who would have been excluded from the temple, Jewish or not, on the basis of his sexual or gender identity. As a castrated man, he was not allowed access to the temple under Deuteronomic law, he was a gender outlaw, scarred and defective, impure and subject to stereotypes. But the prophet Isaiah announces that God will “recover the remnant that is left of my people … from Ethiopia” (Isa. 11:11) and that “eunuchs who keep [the] sabbath” will be welcomed home and will receive “a name better than sons and daughters.” (Isa. 56:4-5) What is at stake for the Ethiopian eunuch, and for many queer exegetes, is not the authority of scripture but its interpretation. Is God the one who authorizes the exclusion from the temple, or the one who gathers the remnant and welcomes the despised and the rejected home? That is the kind of question that requires a guide, an exegete, a theologian. That is the kind of question that, depending how it’s answered, can either end a life or save one.

Black liberation theology set the table for the ever-expanding host of liberation theologies that have followed. My ability to find myself in this text owes a debt of gratitude to the work of James Cone and others who have helped me to know at the core of my being that at the very place where the world turns its back on me, God is with me, God is for me, God is on my side because God sides with the oppressed. And that, likewise, at any place where I would use the name of God to contribute to or continue the oppression of others, that is not true Christianity. It is White Christianity, it is straight Christianity, it is middle-class Christianity, it is respectability-politics Christianity, it is colonial Christianity, and therefore it is not Christianity. You and I, who have been baptized, have drowned to those lies. We rise from these waters as the children of God and joint heirs with Christ of a freedom that cannot be taken away from us. We are fully human. We are alive.

As we prepare to take our leave of one another near the end of another rich, full and difficult school year, pay attention to those who share the road with you. Listen for the phone call that threatens to take you off the path you’d set for yourself. Be prepared to give an account of the faith that is in you, in you, knowing that the right word at the right time can save a life.

Good theology saves lives.

Amen.