The following sermon was preached at First Lutheran Church of the Trinity (ELCA) in the Bridgeport neighborhood of Chicago, IL on Sunday, January 28, 2018 for the annual observance of Reconciling in Christ (RIC) Sunday.

Texts: Deut. 18:15-20 + Ps. 111 + 1 Cor. 8:1-13 + Mk. 1:21-28

Good morning, beloved people of God; and thank you, Pastor Tom, for inviting me to join you for worship on this Reconciling in Christ (RIC) Sunday. You are a congregation that enjoys a strong reputation in our synod for your commitment to issues of justice and your care for one another and your neighbors, so when I got the invitation to preach among you this morning I didn’t really take any time to consider the invitation at all. I just said yes.

I also said yes because, up until relatively recently, I was a parish pastor as well — serving a very small church up in Logan Square, St. Luke’s Lutheran Church of Logan Square, where I was preaching just about every Sunday (at least until we got an intern, which allowed me to sit with the congregation and be fed by someone else’s preaching from time to time). It’s so good to hear the gospel preached by a variety of voices, because we each bring a diversity of perspectives and unique histories to how we share the story of God’s total and unconditional love for each and every one of us. About six months ago, my call to St. Luke’s ended and I began a new call as Pastor to the Community and Director of Worship at the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago (LSTC), which means that I now get to hear a great deal of other people’s preaching … and that I do a good deal less preaching myself. That felt like a vacation for the first two or three months, then I started to itch for the opportunity to preach in the local parish again — because you, dear ones, are the church, you are precious in God’s sight and the world needs you, now as always, to bear the good news of the gospel in a land filled with ancient hatreds, emboldened prejudices, and rising violence.

So let me wrap up all these warming up words with one more thing: a thank you on behalf of the seminary. For many years you have served as a site for field education, welcoming 2nd year seminarians and interns into your community so that they can learn the arts and rhythms of ministry. I’ve known some of the students that have passed through this community and you should not be surprised to hear that they speak about you with so much love and pride when they share the story of First Lutheran Church of the Trinity. You’ve been good for them and, I think, they’ve been good for you. In this, we see once again a small reminder of the greater truth that we are all in this together, each working in the corner of the world where our histories and our relationships give us the power to speak and act with authority to heal the world and its peoples and to liberate one another from all the powers that bind us.

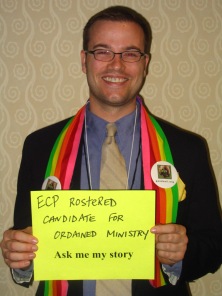

We don’t really know each other, so you might be wondering why Pastor Tom invited me to worship with you on this morning when throughout the Lutheran church many congregations are focusing on the experience of gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and other sexual or gender minorities (which I will from now on refer to, rather clumsily and incompletely, as LGBTQ people and communities) and the church’s painful history and on-going need to be reconciled with the LGBTQ people in our parishes and out in the world who have, for most of history and in most places, heard nothing that sounds like good news from the church. The reason why Pastor Tom likely thought I’d be a good person to speak to this history is that I have been involved in the movement for the full participation of LGBTQ people in the life and ministry of the ELCA for many years.

Like many of you, I was raised in the church. In fact, my father worked for the church as a parish musician for forty years, and I grew up spending two to three nights a week at church for one reason or another. It was my second home and my extended family. So, when I told my dad at the age of 14 that I thought that maybe God was calling me to ministry, he said what I would hope we tell all our children. He said, “Yes, Erik. I know God is calling you to ministry, because God is calling us all to ministry. That’s what it means to be baptized.”

He was right, of course. This is what we Lutherans means when we speak of the “priesthood of all believers.” We mean that, in our baptism, each and every one of us has been called and commissioned to be part of God’s movement for healing, justice, love and liberation in the world. Every single one of us. At a time when the church was focused on concentrating power into the hands and voices of just a few, the clergy, Luther taught that clergy were no more and no less essential to God’s mission than anyone else. We are all called to ministry, each of our ministries being necessary and essential to the world. We are called to be parents and children, teachers and bakers, artists and builders, lovers and friends, because the world needs all of these things, and more. And some of us are called to preach the gospel and administer the sacraments; to proclaim the news of God’s reconciling love, to welcome people at the font and feed them at the table, as a sign that God calls all of us to be reconciled, to welcome one another into the circle of community, and to share all that we have so that all might have enough. It’s just one calling among many. And it was the one I sensed God calling me to.

But not too long after that conversation with my father, I began to sense something else. I began to sense that I wasn’t entirely like other boys my age, that I didn’t see what they saw when they looked at our female classmates. That I didn’t want what they wanted, not in the same way. But it was the 1980s, y’all. And I was in Iowa. So, about the only thing I was hearing about gay people was that they were all getting sick and dying. There were no gay teachers, or gay preachers, or gay politicians, or gay talk-show hosts — no one to show me a reflection of who I might be becoming. I had to figure that out for myself. I’ve sometimes said that it wasn’t so much that I was hiding my truth from the world in the closet, as much as the world was hiding my truth from me in the closet. I was looking for something I couldn’t quite even name, and all the adults who might have helped me out just watched as I stumbled through my childhood trying to name a thing no one wanted to talk about.

It wasn’t until I got to college and met other young adults who were also LGBTQ that I began to realize that my experience wasn’t unique, that I belonged to a community that has been finding ways to flourish in the cracks between the spaces where other people live for centuries. We have been whispering our names, signaling to each other through our songs, sculpting our lives out of the scraps left behind when respectability leaves the table. It was exhilarating and it was terrifying, because it meant leaving so much behind — like my dream of being a pastor in the church. Because I quickly learned that God did not want me in the church. At least that’s what the church said.

But I knew differently, and this is purely a gift from God, that I have always known and never doubted that I belong to God, I was created by God, I am loved by God just as I am. It may the only thing I know for sure, but I know it and I always have. I knew it as a child and I’ve never forgotten it. The only thing time has done to this knowledge is to convince me that what is true for me is equally as true for every one and everything else in all of creation. So I know that you, each and every one of you, belong to God. You were created by God, and you are loved by God, just as you are. I know this for sure.

Meanwhile, I still needed a job, and I found a way to use the gifts God had given me in work that felt almost, but not quite, like what I’d imagined being a pastor might be like. I taught junior high for a year. I worked with homeless and street kids in Minneapolis. I was an advocate with children witnessing and experiencing violence in their homes and in their relationships. My kids were refugees from northern Africa, they were kids tossed out of their homes for being queer or trans, they were kids whose moms were staying in shelters, they were hustlers and they were awesome and I loved them. I loved my work and I loved the people I worked with. But I wasn’t happy, because I wasn’t doing the thing God had put in me to do.

So eventually, in 1999, ten years before the ELCA would change its policies and begin to make room for openly LGBTQ people to serve the church as pastors and deacons, I entered candidacy and went to seminary. My only rule with myself was “don’t lie and don’t hide.” I fully expected to get kicked out at some point, which I did, but I could no longer live with the pain and frustration of being the one to hold myself back from the life God wanted to live through me. If the church was going to reject me, so be it — but I was no longer going to do their dirty work for them by disqualifying myself before I’d even begun.

And this is where, finally, I come to the scriptures assigned for this day. Let’s go back to the Hebrew bible passage from the book of Deuteronomy. Here, Moses is giving the people of Israel instruction on how they will live together as a community in the promised land of freedom after he is gone. He tells them “God will raise up for you a prophet like me from among your people … into whose mouth I will put my words, and that person will tell (the people) all that I command. If any person will not listen to the words which my prophet speaks in my Name, I myself will call that person to answer for this. But if a prophet presumes to speak in my Name a message that I have not commanded to be spoken, or speaks in the name of other gods — that prophet will die.” (Deut. 18:15-20)

How does this passage relate to my story or to our lives? Who is the prophet sent by God following after Moses to share God’s Word with the people? To whom is this scripture referring? Is it Jesus? Or is it … me?

Whoa. I just went there. It’s such a ridiculous, audacious claim to make, but let’s just check it out for a minute. I’ll tell you why I’m led to wonder if I am a prophet sent by God: because people have straight up asked me. When I went through candidacy in the ELCA, a member of the committee said to me, “Surely you know this church’s policies, and yet here you are — clearly living your life in opposition to the teachings and the policies of this church. So, why would you think that the rules would change for you? What do you think you are? Some kind of prophet?”

You know, I’d never considered that question before. It had never even entered my mind to wonder what it meant that I could acknowledge the world as it is, and yet still imagine the world as it could be — even with so much scripture and tradition and policy and procedure standing in the way. I only knew the truth about me and about you, that we belong to God, that we were created by God, and that we are loved by God, just as we are. Those were the things that could not bend in me. Everything else seemed amendable.

So I said to the person questioning me, “It’s not for me to say, whether I’m a prophet or not. Someday we’ll all be looking back, and if gay and lesbian and bisexual and transgender and queer people have found a new freedom and a new place in the church and in the world, then some people will say that this was a prophetic stand. And, if not, then I suppose I’ll be labelled a heretic, and I’ll be in good company. But only the future knows the difference between prophets and heretics.”

And, you know, I would tell you that I have no idea where those words came from, or the courage to say them in that moment, but that would be a lie. Because I knew, even as I was saying them, that those words were the Holy Spirit speaking in me. Because I was telling the truth about my life, not lying and not hiding. And that truth is what I think Jesus was referring to when he said to the people who followed him, “If you continue in my word, you are truly my disciples; and you will know the truth, and the truth will make you free.” (John 8:31-32) Furthermore, I don’t think we’re supposed to run away from the word “prophet,” as if it were somehow thinking too highly of ourselves to imagine that each of us might have an important role to play in the revealing of God’s preferred future for this world, especially when the present is so painfully broken. After all, are we not Easter people? Do we not live our lives in light of the resurrection? Do we not remember Peter’s sermon that first Pentecost day, when he quoted the prophet Joel, saying,

“In those last days it will be, God declares, that I will pour out my Spirit upon all flesh, and your [children] shall prophesy, your youth shall see visions, and your elders shall dream dreams. Even upon my slaves, people of all genders, in those days I will pour out my Spirit; and they shall prophesy.” (Acts 2:17-18)

So, who was God talking about when God said to Moses that God would lift up prophets like him to lead the people into the future? Am I wrong to say that it’s me? No! No more wrong than for me to say that it is you — which I will now say:

You are the prophets anointed by God to lead God’s people into the future! When did this anointing take place? In your baptism! Don’t you remember, “Child of God, you have been marked with the cross of Christ and sealed with the Holy Spirit.” Those are the words the church spoke over you as you were washed with water and anointed with oil. Who are the people God has called you to lead? All people, all of us together. Everyone in, no one left out.

On this RIC Sunday, as I stand in your pulpit — a called and ordained pastor of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America — speaking to you, a congregation with a story of your own to tell about how God brings new life to people and places left for dead, I don’t need to tell you why it’s important to welcome people of all sexual orientations and gender identities into the church. You’ve already done that, and frankly we were always here. What I came here today to remind you of is this:

You are God’s own beloved. You were made by God, and you are loved by God. Just as you are. As is everybody else. Everything else is amendable. So, when you look out at the world as it is, lying to us all about who we are and how deeply we belong to each other, what needs to change?

And who will be the one to say it?

Will it be you?

By what authority?

Who do you think you are?

A community full of prophets?

To me, the answer is a clear as the waters in which you were baptized.

Yes, you are.

“Only the future knows the difference between prophets and heretics.”: Chills, sir, chills! Thanks for another awesome sermon. I miss you and hearing you preach!