Texts: Isaiah 51:1-6 + Psalm 138 + Romans 12:1-8 + Matthew 16:13-20

When we were together last weekend, I shared with you the news that I’d spent last Saturday evening at the hospital with Dea Checchin and her family, gathered around her hospital bed, sharing stories and surrounding her with prayer in the final hours of her life. She died later that night, though I didn’t find that out until after we’d finished worship last Sunday. A couple days later, this past Tuesday morning, my grandmother died. She’d led a long, full life, but the final weeks and days were hard as she labored to deliver herself unto death.

When we were together last weekend, I shared with you the news that I’d spent last Saturday evening at the hospital with Dea Checchin and her family, gathered around her hospital bed, sharing stories and surrounding her with prayer in the final hours of her life. She died later that night, though I didn’t find that out until after we’d finished worship last Sunday. A couple days later, this past Tuesday morning, my grandmother died. She’d led a long, full life, but the final weeks and days were hard as she labored to deliver herself unto death.

Both of these women taught me volumes about faith. On many occasions I shared with Dea my awe at her profound trust that God was with her and had provided enough. Two years ago, as we were moving from the old church building into this new space, she was moving out of her home and into assisted living. On her very first night there, her husband, Lino, passed away. A week later her son-in-law Gary died as well. Yet, when I visited with Dea after these traumas, she was always ready to tell me how fortunate she felt, how God had blessed her with a loving family and had taught her over the course of a lifetime about grace and forgiveness. It was one of the things I loved most about Dea — that, as quick as she was to speak (and often pretty bluntly), she was even quicker to forgive, herself and others. She knew God as the love that redeems, and she was always happiest in worship when we sang the old hymns that proclaimed the mystery of Jesus’ sacrifice for people like her, like us.

My grandma Blanche became my grandma about halfway through my internship year at Holy Cross Lutheran Church in Toms River, New Jersey. Up until then she’d just been a member of my internship committee, who took her responsibilities seriously and made a point of taking me out to lunch once a month to ask how my internship was going and to hear me reflect on what I was learning. About halfway through that year my life got really hard. My great-grand-aunt died, then my maternal grandmother, and then my sister went missing for a month and a half. I felt like the survivor of a great shipwreck, drifting out in the middle of the ocean, alone in a life raft waiting for someone to come looking for survivors. Into that lonely devastation came Blanche who told me that she would be my grandmother. It seemed like a kind thing to say, a gesture of sympathy, but that’s not what it was at all.  For the next fifteen years, Blanche went out of her way to introduce herself to my family and friends. She made a trip in her mid-80s to Des Moines to get to know my parents. At the age of 93 she travelled to Chicago for my and Kerry’s wedding. She taught me a lesson I’ve learned over and over in my life: that all family is chosen family, and that the power of God working through each one of us is the power to create families wherever we are, whenever it’s needed. She knew Jesus as the love that claims us, even when our own flesh and blood may struggle to do so. She also left me with a file folder full of hymns and suggestions for her funeral, which will be a great help when it comes time to plan her memorial service next month.

For the next fifteen years, Blanche went out of her way to introduce herself to my family and friends. She made a trip in her mid-80s to Des Moines to get to know my parents. At the age of 93 she travelled to Chicago for my and Kerry’s wedding. She taught me a lesson I’ve learned over and over in my life: that all family is chosen family, and that the power of God working through each one of us is the power to create families wherever we are, whenever it’s needed. She knew Jesus as the love that claims us, even when our own flesh and blood may struggle to do so. She also left me with a file folder full of hymns and suggestions for her funeral, which will be a great help when it comes time to plan her memorial service next month.

But, however much I loved, respected, adored these women, their faith cannot take the place of my own faith. I cannot know God simply by living in close proximity to people who know God, by singing their songs and praying their words. I’m not saying it doesn’t help. In fact, it’s basically how each of us begins our faith journey, by adopting the words and gestures and customs and rituals of our parents and grandparents, or the friends who brought us to worship, or even the strangers who sit next to us in the pews (which I still feel obligated to say, even though we now sit in stacking chairs — as if all seating, when used for religious purposes, becomes a pew). But, at some point, I have to have my own answer to the question, “Who do you say that I am?”

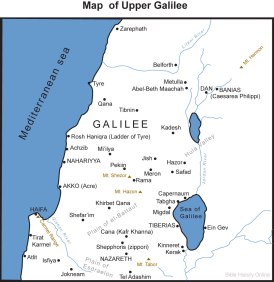

When Jesus asks his followers this question, they have just arrived in Caesarea Philippi. That was the new name for an ancient Roman city far to the north of the Sea of Galilee in the region of the modern nation of Israel called the Golan Heights. “Caesarea” marked it as part of the Roman Empire, “Philippi” referred to Herod Philip II, the son of King Herod who was king at the time of Jesus’ birth and had called for the slaughter of the holy innocents. Philip was also brother to Herod Antipas, the one who had called for the death of John the Baptist.

When Jesus asks his followers this question, they have just arrived in Caesarea Philippi. That was the new name for an ancient Roman city far to the north of the Sea of Galilee in the region of the modern nation of Israel called the Golan Heights. “Caesarea” marked it as part of the Roman Empire, “Philippi” referred to Herod Philip II, the son of King Herod who was king at the time of Jesus’ birth and had called for the slaughter of the holy innocents. Philip was also brother to Herod Antipas, the one who had called for the death of John the Baptist.

All of which is to say that, when Jesus asks those who follow him who they say he is, they are all very aware that they are living in a moment when violent rulers have taken over, rebranding everything around them to serve as a reflection of their own glory, erasing the past and moving against anyone who questioned their authority — including, most recently, John the Baptist. It is in that setting, in a city named for the family that had murdered the man who’d baptized Jesus in the Jordan River, that Jesus asks, “But who do you say that I am?”

His previous question had been easier, when he’d asked what others were saying about him. They simply report what’s being said. “Some say John the Baptist, but others Elijah, and still others Jeremiah or one of the prophets.” Then Jesus sharpens the question, requiring the disciples to step off the sidelines and speak for themselves.

Who do I say Jesus is? I know what my father and mother showed me. I know what I learned in confirmation, and then in seminary. I got a pretty good idea who Jesus was to Dea, and to Blanche. “Some say” a lot of things about who Jesus is, but the question is — who do I say that Jesus is?

Even for me to join Peter in proclaiming that Jesus is “the Messiah, the Son of the living God” isn’t enough, since Peter’s declaration of faith is yet one more instance of received tradition, a formulaic response to a question that is, at its heart, all about relationship. “Who do you say that I am?” How am I the messiah, the long-awaited redeemer of Israel? In what way am I a “Son”? What does it mean to be a child of the “living” God?

Here’s what I believe.

I believe that Jesus was and is the messiah, a word that derives from the Hebrew verb for anointing and was used not only in anticipation of a future ruler, but by various kings, high priests, and prophets throughout Israel’s history. For me it is important to proclaim Jesus the messiah, in part because it means that we are no longer waiting for God to send a savior to create and lead the world I want to live in. In the shadow of Rome, in a city named for a tyrant, Peter declares Jesus to be God’s messiah, and I’m with Peter. I am not waiting for God to send someone else to get us out of this mess. Jesus was baptized by John, and I was baptized into Jesus, and that’s all the authority I need in this life.

I believe that Jesus is the Son of God, which I most often render as “God’s own Beloved,” since that is what the voice from heaven called Jesus, “my Son, the Beloved.” (Matt. 3:17) What’s important about remembering and reclaiming the title of Son, with all its gendered baggage, is that Roman emperors were also called Son of God — not “beloved,” not “child,” but “son,” as a way of making clear the connection between empire and patriarchy: from God to emperor to nation. But I proclaim Jesus, the messiah, as the Beloved heir of God because I believe it is an act of rebellion to say that power does not flow from God to kings, but from God to the oppressed; to colonized people in every land and time, to movements of people that leave what they were taught to do behind and follow the sound of the genuine in themselves and one another until they arrive at that moment when they are called upon to testify to what they have seen and heard.

Which is why it is important to say that Jesus, the messiah, is the beloved heir of the living God, because it makes clear that God did not finish reforming the world with the prophet Elijah, or Jeremiah, or John the Baptist. God did not finish reforming the church with Martin Luther or Martin Luther King, Jr. God did not finish calling people to leave their nets and follow with Peter and the disciples, and God did not finish with me or with us with Dea and Blanche.

God is calling out to you right now to see yourselves as God sees you, as beloved children of the living God, anointed in your own baptisms and called to witness at a moment like this — when once again violent powers seek to erase the history of our land and remake it in their image. In this moment, we are not waiting for anyone who has not already been sent. You and I, baptized into the death and resurrection of the only messiah we need, are the ones we’ve been waiting for.

Jesus says, “I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven.” Does that sound like an invitation to fear, timidity, weakness? By no means! “Then he sternly ordered the disciples not to tell anyone that he was the Messiah.”

And why do you suppose that was?