Texts: Isaiah 56:1,6-8 + Psalm 67 + Romans 11:1-2a,29-32 + Matthew 15:10-28

Jesus called to the crowd and said to them, “Listen and understand: it is not what goes into the mouth that defiles a person, but it is what comes out of the mouth that defiles.”

It was a provocative statement. By referencing “what goes into the mouth,” Jesus is playing identity politics, intentionally provoking the crowd and raising tension in the scene. “What goes into the mouth” is a reference to dietary law, to the Torah, to ideas about purity found in the book of Leviticus. It brings to mind not only laws about what can and cannot be eaten, but who can and cannot be married, who is and is not part of the people called “Israel.” The moment Jesus says, “it’s not what goes into the mouth that defiles” he has issued a very specific challenge to the idea of ethnic nationalism that was a given norm in his day.

Ethnic nationalism. God save us from ethnic nationalism.

You know, that’s not just the plea of a broken and exhausted heart — which is exactly how I expect we are feeling after a week of repulsive demonstrations of racist demonstrations and defenses of white supremacy: broken and exhausted — it is also a description of what is happening in this biblical story. God is saving us from ethnic nationalism.

“It is not what goes into the mouth that defiles a person,” Jesus says. It is not our ideas of ethnic purity and racial superiority that define us, Jesus implies. “But it is what comes out of the mouth that defiles.”

Where to even begin? The things we have heard coming out of people’s mouths in recent days. They turn my stomach. “Blood and soil.” “You will not replace us.” “Jews will not replace us.” Words even more vulgar than these. The rallying cries of the Nazis and the Klan, which we’re supposed to call “neo” to indicate that this is the new incarnation of racism, except nothing about it feels new at all.

Jesus exposes the ultimate consequences of constructing an identity, personal or national, on ideas of race and ethnicity. Because it seems to be almost second nature for us to deride, degrade, despise whatever is different. Jesus says as much in his explanation of the parable, “out of the heart come evil intentions, murder, adultery, fornication, theft, false witness, slander. These are what defile a person.” (Mt. 15:1-28) In other words, we ought to be less concerned with the dangers we imagine others represent, and more concerned with the very real and ever present dangers that live within our own hearts.

Then, in an ironic twist, the scene shifts and we get an illustration of just how hard it is to do the work of uncovering our own biases and prejudices. Having just lectured the disciples and the crowds on the dangers of ethnic nationalism, Jesus encounters a Caananite woman in desperate need of aid — her daughter is being tormented by a demon — and Jesus sends her away precisely because of her ethnicity. “I was sent only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel.” I came to take care of my own. Foreigners go home. Whites only. That kind of talk.

It’s shocking. This is not the Jesus we know, not the Jesus we talk about. This Jesus punctures the myth of perfection we’ve wrapped around history and shows us something troubling. Something, perhaps, we’d rather not see.

How many times over the course of the last two weeks have you heard someone say, “This is not who we are as a nation!” “This is not my America.” But, of course, we know that this in fact is who we are as a nation. This is our America. These are the myths upon which our nation was built. This is the original sin of our birth. We are a nation built on the lie of race. The power and prosperity this country has amassed over the last two hundred and fifty years was stolen from indigenous peoples, extracted from enslaved African peoples, and compounded by exploited immigrant peoples. This is who we are as a nation. Still. Today. As we pursue trade policy that keeps our goods cheap by exploiting foreign labor. As we preserve what we have secured by the threat of violence. You don’t have to march with a tiki torch to benefit from the racism, the ethnic nationalism, that built this country and underwrites the privileges we take for granted.

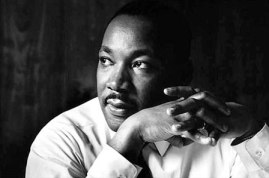

That’s the nature of sin, it captures us in its constructs whether we choose to participate or not. We are not pure or impure on the basis of our individual choices or decisions. We are, as Dr. King said back in 1959, “tied together in the single garment of destiny, caught in an inescapable network of mutuality. And whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly.” He went on to say, “For some strange reason I can never be what I ought to be until you are what you ought to be. This is the way God’s universe is made; this is the way it is structured.”

That’s the nature of sin, it captures us in its constructs whether we choose to participate or not. We are not pure or impure on the basis of our individual choices or decisions. We are, as Dr. King said back in 1959, “tied together in the single garment of destiny, caught in an inescapable network of mutuality. And whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly.” He went on to say, “For some strange reason I can never be what I ought to be until you are what you ought to be. This is the way God’s universe is made; this is the way it is structured.”

It seems also to be part of the nature of our sin that we quickly perceive the ways we are oppressed, but ignore or deny the power we have to oppress others. So Jesus, who is able to see so clearly how the purity codes enshrined in the law of Israel have engendered a spirituality of separatism cannot see how he himself has internalized that ethos. He, who has the power to heal, does not immediately recognize his own power and privilege as he encounters this Caananite woman. As prepared as he was to notice and name the sin around him, he was not immediately ready to confront the sin within himself.

That, of course, is a heretical statement. I’ve just uttered heresy. Mark the date and time. Scripture, elsewhere, says, “God made him who had no sin to be sin for us” (2 Cor. 5:21), and that’s fine for the argument Paul is making to the Corinthians. But here, I think, scripture is showing us something equally true, equally valuable. Something we need to pay attention to and not explain away. Jesus, the Beloved child of God, the one the church has called fully God and fully human, shows us what it looks like when the myth of perfection cracks against the facts of history. When gospel promise meets human prejudice. The one we least expect to participate in the broken structures of human sin, who has just condemned ethnic nationalism and called on those who follow him to watch what comes out of their mouths, calls this woman, a mother fighting for her child’s life, a dog.

You hear the insult don’t you?

He calls this woman, a Caananite woman, a woman of color, he calls her a dog.

You hear the word, don’t you?

This ugliness is in us all. I’m sorry, but it just is. No matter how many workshops you’ve been to. No matter how many friends you have who are Black, or Trans, or immigrants, or disabled. No matter where you studied abroad, or served for a year as a missionary. Our hearts carry the scars of centuries, even millenia, of division. We learn the alphabet of its violent words before we are old enough to speak in subtle gestures, in micro-aggressions. We learn to fear and despise whatever is not us, then we try to unlearn it, then we feel guilt and shame for having been taught it, then we feel powerless to end it, so then we take one of a dozen different paths: we ignore it, we deny it, we rationalize it, we defend it, we embrace it — or we commit to dismantling it, without holding ourselves to the expectation that perfection will somehow be reached this side of eternity.

Jesus, in his humanity, does the thing we have all done. He says exactly the wrong thing. But she does not give up, she argues with him, she takes his insult and turns it back on him. She wrestles with God, like Jacob along the banks of the Jabbok.

And wasn’t it by wrestling with God that Israel got its name? This thing the Caananite woman does, isn’t it so like what Jacob did when he said, “I will not let you go until you bless me!” What would it look like, if a nation, a people, were defined not by adherence to an impossible idea of purity, but by a shared commitment to wrestle together with God, to hold on for dear life until we are blessed, to weave the single garment of destiny, to embrace the inescapable network of mutuality?

For me, it looks like baptism. Ordinary water combined with God’s promise that all people are God’s people. Water that makes us pure, not by erasing our difference, but by washing away everything that hides the image of God native to us all.

This morning we have baptized Sophie Geneva, revealing the truth that she belongs to God. So do you. So do I. So does everybody. We make this claim by faith, trusting in God to heal us all.