Text: Romans 6:12-23

There is a story you already know that is the story you are always longing to hear.

Does that seem possible? If you let your mind search through the cabinet drawers of your heart and your memory, is there a story there you are always longing to hear? Is it a story from your childhood, one of the ones adults placed in your hands filled with archetypes of heroes and metaphors for the lives you could only imagine? Is it a bit of family lore, a founding myth that explains why your people are the way they are? Is it to be found threaded into all the novels and movies and television shows that are streaming into our homes? Is there a story behind all the stories?

There is a story you already know that is the story you are always longing to hear.

What kind of story must it be for you to know it, and for me to know that you know it? What aspect of human existence is broad enough that it can bridge all the differences that divide us? What feature of human life is so universal that a single story about this theme can speak to us all, while still respecting our essential differences?

The story you know, the story you long to hear, is the story of freedom.

Does that seem right? What are our coming-of-age movies — The Breakfast Club, Lean on Me, Real Women Have Curves, heck, even 13 Going on 30 — if not the stories of young people running hard into the predetermined limits of adulthood and striving to achieve a kind of freedom of self-determination at the front end of a long life defined by other people’s expectations for them?

Freedom is the heartbeat of so many other types of stories. In love stories it is the freedom to be ourselves while joining with another. In mysteries it is wed to the theme of truth which is always breaking free of attempts to hide it. In war stories, freedom is the reason offered first for why people are willing to die. In our greatest epics, the stories of our nations, freedom is promise that drives people to leave their homes, to sacrifice their health, to work harder than they’ve ever worked before, to risk their lives and even to give them up, for the hope of a freedom they may never see.

In a version of the world that existed before the internet, or the radio, or even the printing press, our stories were still freedom stories — passed down by memory from one generation to the next. In the first century, just decades after the ministry of Jesus of Nazareth, the apostle Paul could count on his audience having access to these oral traditions, to a common library of shared stories. Among these stories, there was one that perfectly captured their experience of life, that brought together the reality of oppression with the promise of liberation. That story was the story of the exodus of the Hebrew people from slavery under Pharaoh to the promised land of freedom.

For thousands of years we have been telling that story. In fact, it was already ancient by the time John the Baptist appeared in the wilderness calling people out of the city to repent and be baptized. That baptism was a sign of the original passage through water that liberated the Hebrews from bondage in Egypt. Those waters were the starting point for the ministry of Jesus, and that ministry — a life lived freely for others in defiance of empire, which led to the cross but ended with the resurrection — is the defining moment in all of history for Paul’s message to the church in Rome.

For Paul the story of Jesus makes no sense without the story of the exodus. They are of a piece. The God who brought God’s people through the Red Sea and made them free is the God who claims all people as God’s own people through the waters of baptism and liberates them from the power of death which continues to do its best to choke the life out of the world, and each of us as well.

And, just as it took the Israelites generations of wandering in the wilderness to learn to live like free people instead of slaves, so we also are learning to live in the manner of people saved by grace and not by our own slavish commitment to the false idols of this world. The Israelites were free of Pharaoh the moment they set foot on dry land and the waters crashed in on Pharaoh’s armies, but still they looked back at the enticements of their former slavery with longing and grumbled in the desert. So, Paul acknowledges, though we too are already free, having been baptized into Christ, we also struggle to live fully into the reality of that freedom. We, too, look at the world through the logic of our former captivity and long for its rewards — even when we know that those rewards bring us no closer to the freedom we desire, and that they may even hasten our death!

When you tell the story of your life, what is the freedom you long for? When you search your calendar or your credit card statement, what is the evidence you find of your quest for that freedom? Is the manner in which you spend your life reflective of the freedom that is your birthright, or does it show evidence of the habits that distract you from the hard work of liberation?

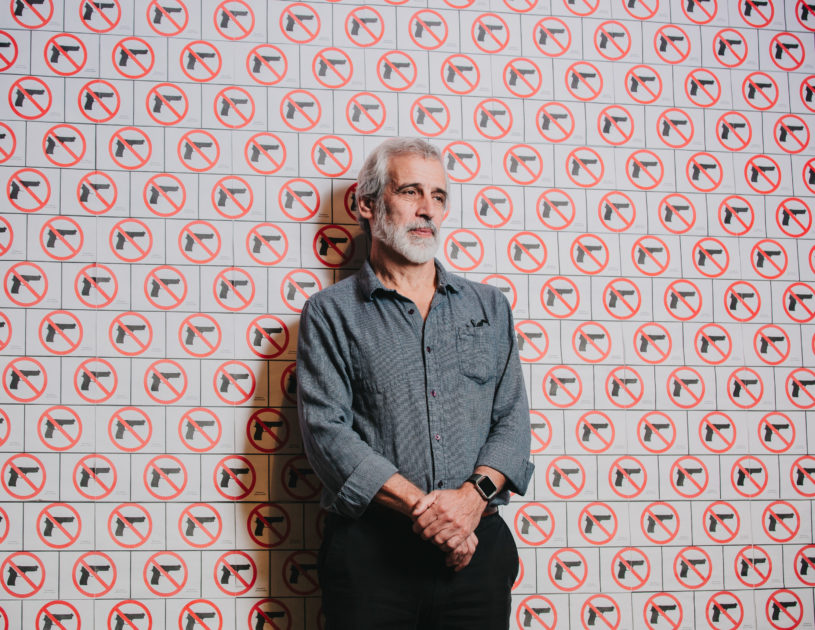

About a week ago I got to meet Jamie Kalven, an award-winning journalist and human rights activist from the South Side of Chicago who has chronicled the deep legacy of police abuses and unchecked power in the city of Chicago and broke the story on the cover-up of the killing of Laquan McDonald. As he spoke to the group of clergy I was with, he recounted to us the history of freedom movements in repressive states, what he called “glaciated totalitarianism.” In such places, like Czechoslovakia under communism or South Africa under apartheid, freedom fighters and dissidents operated on what he called the “as if” principle, asking themselves, “what would happen if we behaved as if we were neighbors?” when, politically, everything was set up to keep that from happening.

The effect he described was the creation of new power. Rather than cowering in fear of repressive power, or sacrificing their vision in order to be granted a small apportionment of corrupt power, people who behaved “as if” their future citizenship had already been secured generated a new kind of power that caught hold of the imaginations of their fellow citizens and launched movements that led to lasting change.

What would happen in your life, in our life together, if we acted “as if” we were already free of the forces that oppress us, of the stories that overwrite us with a vision for our lives that is not our own?

There is a story you already know that is the story you are always longing to hear. If you were to live your life as if that story is true, what would have to change? What do you think? Shall we live “as if” …