Texts: Ex. 12:1-4,11-14 + Ps. 116:1-2,12-19 + 1 Cor. 11:23-26 + John 13:1-17,31b-25

Last fall, on November 9th — the day after the elections — St. Luke’s opened its doors for those who needed a place to pray, to weep, to talk, to be silent, to sing as we tried to make sense of an election that caught millions of people by surprise. My memory of that night is that people were shocked that their fellow citizens had elected to this nation’s highest office someone who showed no regard for values they held as central to our national identity. As they processed their shock and shame, it seemed to me that part of what they felt was a sense of betrayal by their neighbors; that they had been living under the assumption that the majority of people in our nation shared their outlook on the world, and that this assumed solidarity had been betrayed.

Once the shock subsided, there was no shortage of articles and essays attempting to make sense of the 2016 election. We were told that the surge from the right-wing of the American electorate was also acting out of a sense of betrayal — that the government created to serve and advance their interests had been co-opted by a liberal agenda dominated by identity politics and dedicated to a form of corporate globalism that devalued American labor and left the White working class behind. People who’d felt betrayed by their country rose up to take it back, we were told.

Betrayal is an odd and painful thing. It can only exist where there is the assumption of some form of solidarity. To be injured by one’s enemy isn’t a betrayal, it’s an assault. To be injured by one’s parents or children, however, is a betrayal of the bonds of family. To be fired without cause is a betrayal of the bonds built by shared effort. To be cheated upon by a lover or spouse is a betrayal of the bonds of love or the vows of marriage. To be neglected by a friend is a betrayal of the bonds of friendship. Betrayal assumes relationship, loyalty, solidarity, even love.

One of the effects of our modern, mobile, industrial life is that the number of people and communities we invest in as adults has, for many people, diminished. I could be wrong, but it seems to me that when I was younger I used to hear more anger and betrayal at how companies no longer treat their employees with any sense of loyalty. People who gave decades of their lives to help build a company up — only to find themselves laid off, replaced, or otherwise treated as expendable — used to express more of a sense of betrayal and outrage. Now it seems to be taken as a fact that companies have no commitment or obligation to their employees beyond what can be legally mandated.

Similarly, as a child I remember the sense of dismay people had over the rising divorce rate. In 1980 about half of all first marriages ended in divorce. Over the last thirty years the divorce rate has fallen, though it also seems that the expectation that marriages survive the trials of life has as well. People speak jokingly of “starter marriages” the way they might speak of “starter homes.” If we enter into our most intimate relationships with low expectations, how deeply can we feel betrayed when they finally end?

The year that I lived in Washington, D.C. I remember attending a party and overhearing a conversation in which someone remarked that they were on their “third set of friends” since moving to the Capital because of how quickly people come and go from that place. Today it seems to me that many people and many places experience that kind of transience as commonplace. Could anyone even feel betrayed by a friend or neighbor’s decision to move on? Can we imagine being invested enough in one another to feel a sense of betrayal in any relationship outside of work or family?

Or, just how far do we imagine our self-interest extends?

Over the course of his three years of public ministry, Jesus had built a community of people who were deeply invested in him and in one another. By leaving his family at home to wander the countryside with his disciples, Jesus had already betrayed societal norms for how men and sons were supposed to behave. By associating with women and foreigners and all manner of sick and diseased people, Jesus had betrayed religious norms for how observant Jews were supposed to act. By entering Jerusalem on the back of a donkey to the cries of those who named him “the King of Israel” he had betrayed the political norms for how occupied people were to supposed to relate to the government. But, however outrageous their behavior may have seemed to those outside their community, within the circle of those who followed Jesus there was a sense of solidarity with a new vision for how the world might be. A vision of food for the hungry, healing for the sick, dignity for the poor, justice for the oppressed, and welcome for the foreigner. It was a vision that bound them to one another and to Jesus like branches to a vine.

This is what makes this scene so dramatic, and potentially explosive. After three years of laboring alongside one another for a future none of them had ever seen, but all were hungry to behold, we learn that one of the disciples — Judas — has put a plan in place to betray Jesus. More than that, we know that Peter — always eager to prove his devotion to Jesus and the cause — is about to publicly deny Jesus. What do we expect at this moment?

If it were any other story, instead of a story about Jesus from a source we call the Bible, we would expect a fight. If this were a scripted drama on HBO, like The Sopranos or Game of Thrones, we would expect the traitors and cowards to get killed. If this were American politics, we’d expect someone to get scapegoated. If this was a workplace scene, we’d expect someone to get fired. In any other situation, we would expect the person with the power to use it to their advantage. We should expect Jesus, into whose hands God has “put all things,” to flip over the table and drive the faithless disciples out of the room.

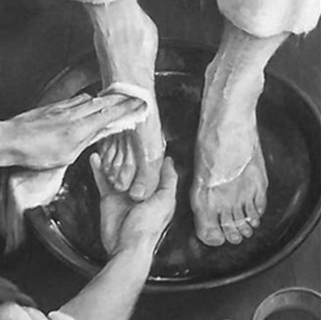

Instead Jesus rises from the table and, instead of flipping it over, he goes from person to person and washes their feet. He takes the job that would have been given to a servant or a slave, and he does that work for everyone in the community, knowing full well the ways that they will fail him and themselves. This, he calls the “new commandment” — the newness coming not from the command to love, but to love humbly, to love unconditionally, to love even those who betray and deny us, to show our love in acts of service we might wish someone else would do in our place.

Instead Jesus rises from the table and, instead of flipping it over, he goes from person to person and washes their feet. He takes the job that would have been given to a servant or a slave, and he does that work for everyone in the community, knowing full well the ways that they will fail him and themselves. This, he calls the “new commandment” — the newness coming not from the command to love, but to love humbly, to love unconditionally, to love even those who betray and deny us, to show our love in acts of service we might wish someone else would do in our place.

How different our world might look if this was our response to betrayal. How different our conversations might sound, over coffee and online, if we trained ourselves to respond to anger with and resentment toward our fellow citizens with acts of service rather than blame and shame. How different our relationships with family members and co-workers might be if we stopped trying to win arguments or approval and just did the work that no one wants to do.

How different life could be, for all of us, if we met betrayal with love.

I believe we are living in the moment of betrayal. I actually believe we are living in a constant state of betrayal so deep and so persistent that most of us have numbed our hearts and distracted our minds so that we don’t have to feel the rage and heartbreak that come from expecting something more out of life. What has been betrayed is our humanity, what has been sacrificed is the memory that we were made in the image and likeness of God. We were not made for terror and anxiety. We were not made to fear our neighbor and hate the stranger. We were not made to rise or fall on the basis of our ability to accommodate ourselves to a system that ridicules us as we learn, that punishes us as we age, that uses us when we succeed, and that abandons us when we struggle or stumble. We were made for community. We were made for each other. We were made for love.

But the only way we will ever live in a world fit for lovers is if we band together to change the way things are, which means building something big enough and powerful enough to confront the powers and principalities of this world and to call them back to their original purposes — supporting and sustaining life for us all. That job is bigger than any of us can tackle alone. If we want to see that world, we will have to be willing to invest our time and our trust in one another. We will have to build relationships that matter enough to us that we are willing to risk being disappointed (again), being betrayed (again).

And why would we ever do that? Why would we ever risk the pain of putting ourselves out there over and over, knowing that we will certainly be betrayed and denied; knowing that we ourselves will sometimes be the ones who betray or deny the vision we are working toward? Why would we risk the humiliation and retribution that come from failing in front of our families, in front of our friends and neighbors? Failing on the world’s stage?

Let me ask this:

What would you be willing to risk, if you knew that failure would be met with love?

And, what would it take to convince you that no failure of vision or of nerve, no betrayal or denial, could break that love?

And, how often would you need to be reminded of that love?

This is what we say to each other within the community of the church about failure:

“On the night in which he was betrayed, our Lord Jesus took bread, gave thanks, broke it, and gave it to his disciples, saying: ‘Take and eat, this is my body, given for you, do this in remembrance of me.’”

Every Sunday, every week, every time we return to this table we remember that God meets our failures, our denials, and our betrayals with the self-giving love of Jesus, who knelt to wash our feet and commanded us to love one another like that.

Don’t you long to live in a world that loving, that forgiving, that free?

That’s what we are building together — each meal shared, each foot washed, each person loved more deeply than any betrayal can deny.

Amen.