Texts: Isaiah 43:1-7 + Psalm 29 + Acts 8:14-17 + Luke 3:15-17,21-22

What is baptism?

I know I’m supposed to have a good answer to that question, but I suspect it’s the kind of question that requires an experience rather than an answer.

I know what I was taught about baptism, what Luther wrote in the Small Catechism that some of you had to memorize as part of your confirmation in the church decades ago:

What is baptism? Baptism is not simply plain water. Instead, it is water used according to God’s command and connected with God’s word.

What then is this word of God? Where our Lord Christ says in Matthew 28, “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit.”

What gifts of benefits does baptism grant? It brings about forgiveness of sins, redeems from death and the devil, and gives eternal salvation to all who believe it, as the words and promise of God declare.

What are these words and promise of God? Where our Lord Christ says in Mark 16, “The one who believes and is baptized will be saved; but the one who does not believe will be condemned.”

Luther goes on to reflect on how it is that water is able to accomplish these things (“clearly the water does not do it, but the word of God, which is with and alongside the water…”), and what this baptism by water signifies (“that the old person in us with all the sins and evil desires is to be drowned and die through daily sorrow for sin … and that daily a new person is to come forth and rise up to live before God in righteousness and purity forever.”)

I don’t dispute any of what brother Martin had to say on the topic, but I will confess that it doesn’t speak to me. There is a kind of mechanism to his formula that reduces the sacrament to a series of “because/therefore” and “if/then” statements, which doesn’t reflect my own experience of being a baptized person. Because Jesus said, “make disciples of all nations” therefore we baptize. If we are baptized and believe, then we are saved;” and, conversely, “if not, then we are condemned.”

The reality, I suppose, is that two thousand years into this project of God’s called “Christianity,” it has become impossible to think about or talk about baptism without dragging all of the baggage of all of the church’s teachings on the subject into the conversation — which, and this is no shocker to anyone, has been all over the place and not terribly consistent. But even more than the teaching, it has been the practice(s) of baptism that have left many of us inherently suspicious. Making disciples “of all nations” sounds quite a lot like colonialism, the mass exportation of values and power relations onto foreign people without regard for their own histories and experiences. I think that for many of us, much of our discomfort with the idea of evangelism comes from the really healthy acknowledgment that humanity’s track record of respectful engagement with people of different cultures and practices is spotty at best. We are rightfully cautious about the sorts of religious chauvinism that so quickly creep into our every effort to share the faith that is in us, so that more often than not we share very little about our faith at all preferring to keep private what we have been commanded to carry into all the world.

But the idea of “nations” is baked into the concept of baptism from the very start in ways that I think are also profoundly important, for reasons that are hinted at in this morning’s scriptures beginning with Isaiah.

“For I am the LORD your God, the Holy One of Israel, your Savior. I give Egypt as your ransom, Ethiopia and Seba in exchange for you. Because you are precious in my sight, and honored, and I love you, I give people in return for you, nations in exchange for your life.” (Isa. 43:3-4)

Even with all its passionate language and declarations of love, there’s something really disturbing about this passage, which sounds somewhat like a prisoner exchange between sovereign nations. God is named the Holy One of Israel to the exclusion of Egypt, Ethiopia and north Africa.

We resonate with “do not fear, for I have redeemed you; I have called you by name, you are mine” which sounds like a more eloquent version of “little ones to him belong, they are weak but he is strong.” But the question of belonging always seems to beg the more difficult question to answer: are there others who do not belong to God? If so, how do we know? What is the marker, what is the sign?

The insider/outsider tensions evidenced in Isaiah show up in a slightly different form in the story we get from Acts (and not Ephesians, as your bulletin would mistakenly have you believe), moving from international conflict to ethnic prejudice. The tension is set up right away between the apostles in Jerusalem and the Samaritans, who we know from any number of other biblical references are the much despised and maligned ethnic group living within the borders of the nation but on the margins of respectability. They are the butt of every joke, they are the target of every slur. Yet, despite all this, they have heard the story of the life and death and resurrection of Jesus as a narrative of good news for them as well and have already been baptized in Jesus’ name — though there is apparently some dispute about whether or not the Spirit had been active in that baptism, because Peter and John are sent to go and pray with them, to lay hands on them and touch them, at which point they received the Holy Spirit.

I suppose there’s a way of reading this story that focuses on Peter and John as the necessary mediators of God’s Holy Spirit, that reinforces the old power dynamic between those living in Jerusalem and those from Samaria, but to use that detail as the starting point for interpreting the story ignores the larger frame of reconciliation between ancient enemies. The bad blood between Israel and Samaria goes back to the Babylonian exile. It is an ancient enmity. Yet somehow they see themselves in the story of the confrontation between Jesus and the Roman Empire, and they come to faith. The timing of the arrival of the Holy Spirit emphasizes the disruption of established national and cultural identities in that it is only when these old enemies finally sit down in the same room and lay their hands on one another, touch one another, become real to one another, that the Spirit of God is felt among them.

My struggle with the way the church has taught about and practiced baptism for so long is that it reinforces the very sense of nationalism I think the sacrament is intended to disrupt. We say, “go therefore and make disciples of all nations” through baptism, but we imagine baptism as a new nationality, a new preferred status with God that still leaves some people chosen and others condemned.

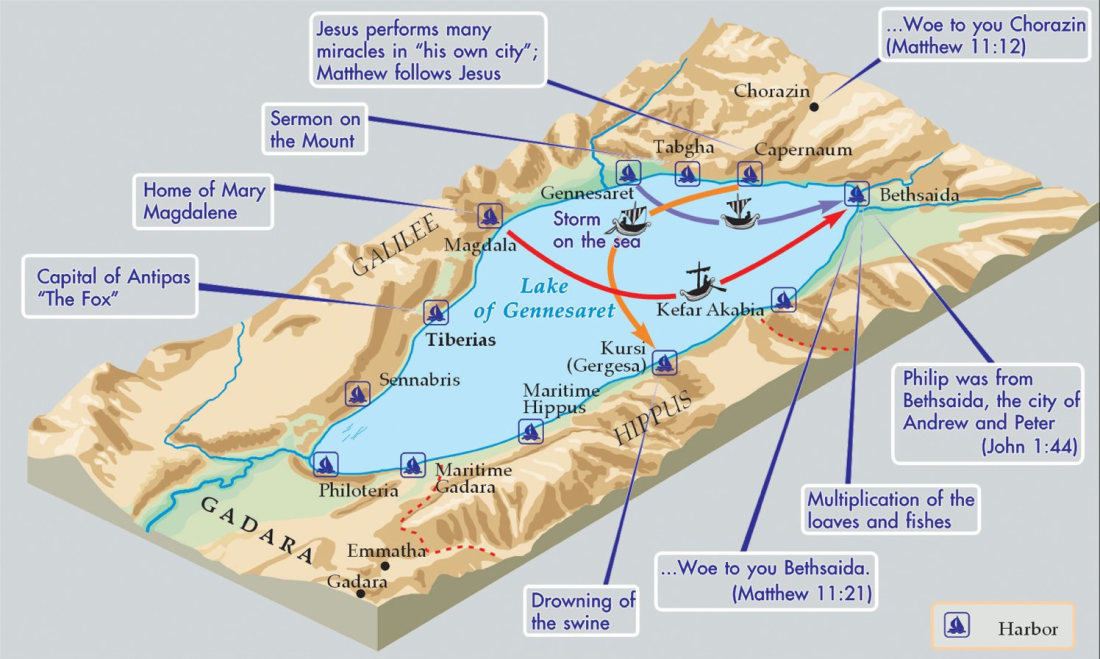

But the story of Jesus is the story of God’s love overflowing every boundary we construct to contain it. The ministry of Jesus criss-crossed the shores of the Sea of Galilee so that he could eat with, and touch, and heal people on every side of that pool of water.

But the story of Jesus is the story of God’s love overflowing every boundary we construct to contain it. The ministry of Jesus criss-crossed the shores of the Sea of Galilee so that he could eat with, and touch, and heal people on every side of that pool of water.

My heart suspects that there is something hard-wired into us that keeps trying to break the world into “us” and “them.” It must have something to do with our most basic survival instincts. I say “my heart” because that’s where I feel it, this seemingly genetic predisposition to be suspicious of others, to try and break the world back into tribes.

The call to “make disciples of every nation” by baptizing them can so easily become one more way of practicing that old human impulse, but that is not what this sacrament is intended to do. It’s not a new passport issued by a different sovereign. It is the abolishment of borders. It reminds us that every human being comes into this world surrounded by waters whose headstream is God. It is water combined with God’s word, because we are creatures of flesh and spirit. We need to touch something in order to believe that it’s real.

So we touch this water remembering that it is holy because it comes from God, just as we are holy because we come from God, just as every life is holy because every life comes from God. God, present in the waters that have surrounded us even before birth, has been whispering into each and every heart, “you are my child, you are beloved, with you I am well pleased.”

As we come to believe this, as we begin to order our life together in this world around this idea that all life is sacred, then we are all saved — together. As long as we continue to live in scarcity, treating love and belonging and all the rest of life’s basic necessities like privileges instead of birthrights, we are condemned — together.

We are all in this together, which is why we do not generally practice private baptism, because it confuses the meaning of the sacrament. You aren’t baptized so that you can be set apart from other people, you are baptized into Christ, who lived and died for all people. In these waters we die to all the lies that have kept us divided, and we rise to a new life, a new holiness, a new discipleship, a new practice, a new nation which is no nation at all. We are citizens of one another’s welfare. We belong to God.

Amen.