Texts: Isaiah 63:7-9 + Psalm 148 + Hebrews 2:10-18 + Matthew 2:13-23

Merry Christmas everyone! We are still in that season of Christmas which spans the 12 days from December 25th through January 5th, after which we celebrate the Epiphany of our Lord (which we’ll do in worship next Sunday, though technically it falls on Monday, January 6th).

It’s only been a couple of days many of us have seen each other and, whether you were here for the Christmas holidays or off traveling, I hope you were able to enjoy time with family or friends. Kerry and I left immediately after worship on Christmas morning for Des Moines, where my family lives, and got back early last night. It was a brief visit, so we had to pack lots of holiday traditions into just a couple of days.

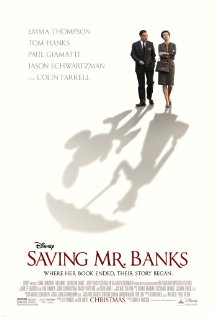

One of those traditions is the holiday movie. Hollywood times the release of all sorts of movies to coincide with the winter holiday, knowing that families will be together and looking for entertainment, and our family is no exception. This year we decided to see the recently released “Saving Mr. Banks,” which tells the story of the woman who wrote Mary Poppins, P. L. Travers and the efforts of Walt Disney to bring her story to the silver screen. Travers is played by the magnificent Emma Thompson and Disney by Tom Hanks, and the cast is filled out by a host of fantastic actors working with a wonderful script. When you’ve got Mary Poppins, Walt Disney, Emma Thompson and Tom Hanks all in one place a good time is sure to be had by all, right?

Pretty quickly we discovered that “Saving Mr. Banks” wasn’t after a good time at all. We’d gone in expecting a fairly straight-forward contest of wills between Travers and Disney, only to discover that the real story in “Saving Mr. Banks” (as the title implies) is about the relationship between Travers and her long-since-deceased father — an imaginative, free-spirited man plagued by alcoholism and trapped in a career as a banker that is slowly killing his soul. As the movie unfolds, we begin to see that Mary Poppins was the story Travers created to bring order to the chaos of her own childhood by creating a fantasy, a dream, in which all that had been lost to her — her childhood, her father, her joy — could be restored.

The texts for the First Sunday of Christmas this year have a similar kind of “bait-and-switch” quality to them. We come to worship just days after Christmas, expecting perhaps a quiet resolution to the story that began on Christmas Eve as the infant Jesus is born in a stable in Bethlehem. Instead we get a nightmare of a story about paranoia and anger that results in the deaths of a generation of children.

“Saving Mr. Banks” begins with a quote from Mary Poppins delivered by Bert the chimney sweep,

Wind’s in the east, mist coming in, like something is brewing … about to begin. Can’t put me finger on what lies in store, but I fear what’s to happen all happened before.

The gospel of Matthew might well have prefaced its version of Jesus’ birth with the same words. If parts of the gospel reading seemed somehow familiar, that’s because you’ve heard them before in Hebrew scripture, in Genesis and Exodus. Once again we have a character named Joseph whom God communicates with in dreams who must flee to Egypt in order to escape the wrath of his own countrymen. Once again we have a child rescued from certain death, as Moses was when his mother set him in a basket on the river, while a generation of children are slaughtered. Echoes of the past are heaped onto this story, layer after layer. Not only is Joseph, the husband of Mary, like Joseph, the son of Jacob whose name became Israel; not only is Jesus, like Moses, spared the wrath of a violent and vengeful ruler; but we also hear the name Rachel, Jacob’s wife, who the prophet Jeremiah imagines as weeping for her children, the entire nation of Israel, during their long exile in Babylon.

The gospel of Matthew, like Bert the chimney sweep in Mary Poppins, sees what is happening as Jesus enters the world and wants us to recognize that the story to come, the story of Jesus’ coming into the world, is tied to the never-ending story of God’s saving power. “Can’t put me finger on what lies in store, but I fear what’s to happen all happened before.”

For many, this story of the slaughter of the holy innocents — which only appears in Matthew — is a passage they’d rather avoid. There’s simply no way to stay lost in the soft glow of the star of Bethlehem and the shepherds and the angels chorus as you read about the Holy Family turned into refugees on the run from unchecked and state-sponsored violence. But, for those who have lived this story, who know what it means to be a refugee, to be on the run and in hiding from the people or the nation who was supposed to love and care for you, this story is one of hope and ultimately of redemption.

Here in Chicago, RefugeeOne works with almost 2,500 refugees every year, helping acclimate them to a new culture, a new language and a new life as they flee from violence, war and persecution in their homes. Currently the majority of these refugees are Iraqis who helped the recent U.S. military operations and Assyrian Christian Iraqis fleeing religious persecution; Burmese who have fled government-instilled violence and persecution; and Bhutanese who have fled ethnic “cleansing.” Many of these people were raised in nations antagonistic to the United States and our allies, so this resettlement feels very much like the Holy Family might have felt as they entered Egypt, the land of their people’s former enslavement.

But the experience of fleeing from violence at the hands of your countrymen, your family, is not limited to those escaping from political violence and repression. For millions of people right here in our own country, there is no safety even in their own homes. Research on domestic violence tells us that, globally, one in three women is beaten or abused, most often by a member of her own family and that domestic violence is the leading cause of injury to women — more than car accidents, muggings and sexual assaults combined. Studies suggest that up to 10 million children witness acts of domestic violence annually, and that this early exposure to violence can lead to a continuing cycle of violence, particularly as boys exposed to violence as children become adults.

There are so many ways to lose a generation to violence.

So, to people such as these, to refugees and immigrants and all who are on the run from the violence of their own past, the first word of good news in the hard story from scripture this morning is that God is intimately aware of your suffering, and that God’s own child knew firsthand the struggle of finding yourself a stranger in a strange land. Jesus was a refugee, and escaped from the kind of genocidal violence that still continues to this day.

“Can’t put me finger on what lies in store, but I fear what’s to happen all happened before.”

One of the fascinating elements of the movie “Saving Mr. Banks” is the way the main character, P. L. Travers, struggles with the ongoing influence of her childhood on her present reality. She is at once very much her father’s daughter, blessed with a rich imagination that is able to see the enchanted aspects of everyday life, and she is his opposite: stern where he was warm, aloof where he was familiar, and unyielding where he was forgiving. That dichotomy shows up in Mary Poppins in the characters of Bert, the lovable chimney sweep and Mr. Banks, the children’s overly-responsible and absent father. As the film moves towards its resolution, Travers is confronted with the realization that she has become stuck in her own past, trapped by a fantasy of who she was and who she is.

When we examine our own dreams, the ones that come to us at night, wild and uncontrollable, it’s often been suggested that we entertain the idea that we might be any of the characters in our dreams and not only the one from whose point of view the dream seems to be taking place. So P. L. Travers is not simply Mary Poppins, or Bert, or Mr. Banks, or his daughter Jane. She is all of them, trying to come to a new resolution of an old story.

Likewise, when we listen to the story from Matthew, which reads like a nightmare, we are led to wonder if we might not only be like Jesus and his family, or like those wise men from the east, but also how we might be like Herod and, if so, how we might come to a new resolution of that old story.

In the verses just before the ones we read this morning, we hear about Herod’s first encounter with the wise men. Upon their arrival, they announce that a child has been born who is king of the Jews. This was actually Herod’s title, given to him by the Roman Empire, by whose power he was allowed to govern Israel in Jerusalem. His first response to the news of this infant child is fear, fear that someone has come to replace him. His second response is dishonesty, as he tells the wise men that he supports their efforts to find the child and, in fact, would also like to go and pay the child homage. His final response is anger, which controls him, and leads to the death of Israel’s children.

The truth in the telling of this story is that fear so often leads to anger, and that those who cannot face their own fears are prone not only to violence but to deception as they justify their abuses to themselves and others. This happens in settings as vast as the relations between nations who build up stockpiles of weapons to gain leverage in their relationships with one another rather than working together to find common cause and support the common good; and as intimate as our own homes as fearful spouses justify hurtful words and painful actions with excuses that justify their behavior.

We may not be kings, like Herod, or Pharaoh, but we each exercise some measure of power in our respective lives. And we each, to some extent, misuse the power entrusted to us, whether that be at home, at work, or out in the wider world. Which is why we so often begin our worship with the act of confession and the assurance of forgiveness. Our constant confession is not an effort on the part of the church to shame those who gather here, but to liberate them from the guilt that — when we are honest with ourselves — plagues all of us who have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God, in whose image we are made.

At one point in the movie, as the script and song-writers keep working to translate Travers’ book into a film, Travers gets fed up with their efforts to capture the essence of Mary Poppins and her relationship to the Banks family and storms out of the room saying, “You think Mary Poppins is there to save the children?”

I think that’s where I so often get stuck in my effort to interpret this story of the slaughter of the holy innocents. I am outraged by the suffering of so many children, and I want God in Jesus to save them. But, in God’s eyes we are all the children, even the grown ups, even the violent and abusive ones, even Herod. Mary Poppins came to save Mr. Banks, just like Joseph spared his family by taking them to Egypt, just like Moses saved the people of Israel by leading them out of slavery, just like Jesus saved us all by bringing an end to a system of sacrifice in which each sin had to be paid for with blood, an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth. In Jesus God is saving us all, the holy innocents and the fearful, violent offenders. All of us.

It is such a strange story, so unconventional in its plot and execution that it’s hard to believe, and perhaps we wouldn’t except that it keeps happening over and over and over again. Us getting lost in our fear and our anger and our violence, and God finding us and saving us time and time again.

And I trust what’s to happen has happened before.

Amen.