Texts: Jeremiah 23:1-6 + Psalm 46 + Colossians 1:11-20 + Luke 23:33-43

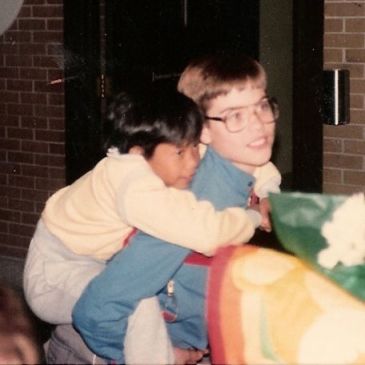

My sister was six years old when my family adopted her from Thailand. For six years she’d eaten Thai food, watched Thai television, played with Thai children, and — most importantly — spoken Thai. Imagine yourself at age six: how much you’d already grown, and learned, about who you were and what could be expected from the world around you. Now imagine all of that changing essentially overnight.

My folks and I flew to Bangkok, Thailand and spent about a week getting to know Tara before bringing her home with us. First, a visit to the adoption agency where we spent a few hours together. Then, a sight-seeing day-trip, supervised by her social worker. Finally, an overnight at the guest house where we were staying. Then she was on a plane with us, heading to the United States, where everything was different. The food, the weather, the big house with a private bedroom she didn’t have to share with anyone else, and Jesus.

Tara learned her English in bits and pieces. Names of foods and people and places came first. Simple verbs in the present tense. Our early conversations were very basic, no abstract concepts. “I want pancakes,” or “We go church.” So, when Tara burst forth with her first theological question, it was memorable.

We were sitting around the dinner table preparing to eat with the same prayer I’d been saying every night since I could remember: “Come, Lord Jesus, be our guest, and let these gifts to us be blest. Amen.” Suddenly, Tara asked, “Where Jesus? We eat, we say Jesus. We sleep, we say Jesus. I no see Jesus. Where he? He hiding?”

When the apostle Paul writes, “He has rescued us from the power of darkness and transferred us into the kingdom of his beloved Son…” (Col. 1:13) it reminds me of my sister’s experience of coming to the United States — not in the sense that Thailand was somehow a place of darkness, or the United States an outpost of the reign of Christ. Just that, I have a memory of how hard that transfer was for Tara, every day being surrounded by sights and signs and symbols for things she’d always known and done, but being forced to see them and speak about them in a new way. Even her name was new in this new place.

The same is true for we who bear the name of Christ. We live and move and have our being in a world filled with foods, and rituals and relationships, but we are asked, over and over, to see them and speak about them in a new way. The man who shuffles slowly down the sidewalk, talking to himself, we call brother. The woman whose work is paid under the table, and not well enough to support her family, we call sister. The child whose swagger and swearing is intended to push us away we invite in, and call friend. The water that welcomes us into this house changes our names. The food we eat at this table goes by the name Jesus.

“Where Jesus? We eat, we say Jesus. We sleep, we say Jesus. I no see Jesus. Where he? He hiding?”

Paul goes on to say, “He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation; for in him all things in heaven and on earth were created, things visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or powers — all things have been created through him and for him. He himself is before all things, and in him all things hold together.” (Col. 1:15-17)

There’s something ironic to me about the fact that it is Paul, and not Peter or one of the other apostles who had accompanied Jesus during his earthly ministry, who says, “he is the image of the invisible God.” Paul, who had never laid eyes on Jesus, who was blinded as he traveled the road to Damascus, who heard the voice of Jesus asking him, “why do you persecute me?” This Paul is the one who says, “he is the image of the invisible God.”

Paul knew in his own flesh what it meant to be rescued from the power of darkness and transferred into the reign of God. He, who had been a violent opponent of the Jesus movement, who was present at the stoning of the apostle Stephen and approved of his murder, who entered home after home of the church in Jerusalem, and threw its men and women into prison, he was the one God chose to carry the message of reconciliation out from Jerusalem to the far corners of the known world. Someone who had never laid eyes on Jesus.

The reign of God is not like anything we have been taught to expect in this world. The gospel of Luke, which we have been reading throughout this past year, and which we will soon set down as we prepare to begin a new year in the life of the church next week as Advent leads us into the gospel of Matthew, has presented us with parable after parable about the foreignness of God’s reign of forgiveness. The reign of God is like a father who forgives his son for wasting the family fortune, and welcomes him home with open arms. The reign of God is like a shepherd who foolishly leaves ninety-nine sheep alone to go after the one who is lost. The reign of God is like a wealthy man who throws a party, and invites the poor, the blind and the weak to enter his house. Images of the reign of God.

Jesus’ own life has read like one of his parables. After being baptized at the Jordan, and being named God’s Son, the Beloved, Jesus wanders in the wilderness where he is tempted, three times, to use that mantle, that power to distance himself from God’s people. Those three temptations are mirrored again at the end, in the final passage we will hear from Luke’s gospel this year. Now Jesus is on the cross, and three times he is mocked by those who are killing him, “save yourself!”

They have fundamentally misunderstood him, Jesus, the one whose name means “God saves.” Because he did not come to save himself. He came to save a world full of common criminals. As common as you and me. Even on the cross, in the hour of his death, Jesus looks with mercy on a man who confesses that he is getting exactly what he deserves for his crimes, and says, “today you will be with me in paradise.”

But this is the kind of God we have come to know in Jesus. The kind of God who looks at a criminal with compassion, sealing his record so that his sins might be forgiven and he might enter with joy into the paradise of communion with God.

Maybe Paul, who never saw Jesus, but laid eyes on so many who followed him, heard that story, the one about Jesus forgiving the criminal on the cross. I don’t know if that’s true or not, but somehow he went from being the kind of man who persecuted Christians to the kind of man who voluntarily stayed in his prison cell to spare the life of his jailor and to witness to the power of God to heal and transform every place on earth, even the ones we imagine to be God-forsaken — like our prisons, and their execution chambers.

Paul’s letter to the Colossians is one to people he also had never seen, only heard of through the testimony of the rest of the church as it spread across the Mediterranean. He writes to them to encourage them in their faith, to exhort them to exercise judgment in separating the ways of the world from the ways of Christ Jesus, and to call them to love. The verses we’ve heard this morning sound an awful lot like a creed, in that they are a series of propositions about who Christ is — the head of the body, the church; the beginning, the firstborn from the dead in whom all the fullness of God was pleased to dwell, and through whom God is reconciling all things, making peace through the cross (Col. 1:18-19).

Language is learned through repetition. We didn’t have a way to answer Tara’s questions, “where Jesus? He hiding?” given the vocabulary she had at the time. All we could do was to keep bringing her to church. Here she began to pick up fragments of songs, phrases that she could remember: “worthy is Christ, the Lamb who was slain, whose blood set us free to be people of God” and “Lord God, lamb of God, you take away the sin of the world. Have mercy on us.”

Soon she began to understand who Jesus was, where he was, even though she hadn’t seen him. Like Paul hadn’t seen him. Because she saw the cross, and later she spent some time on it, like you and I have. And, oh, what mercy God has shown to each of us in those moments when we have found ourselves in the worst of our suffering — even suffering we can admit, like the criminal who hung next to Jesus, is sometimes the just punishment for our misdeeds. Because God did not send Jesus to save himself, but to save us. To rescue us from solitude and restore us to community. To reconcile us to God and to one another. To bring vision to our downcast eyes by lifting them to the glories of a paradise where all are welcome, regardless of their past or their present. To follow us and to find us and to finally bring us home.

This is Jesus, who is not hiding, but is with us. Now and forever. Thanks be to God!

Amen.