Texts: Job 39:1-12,26-30 + Psalm 104:14-23 + 1 Corinthians 1:10-23 + Luke 12:22-31

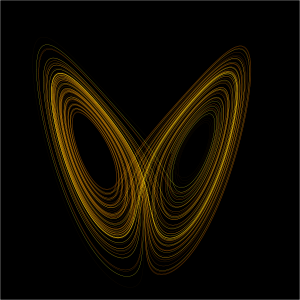

You’ve heard of the butterfly effect, right? Aside from being the title of a mediocre Ashton Kutcher movie from a decade ago, the butterfly effect is the popular name for a phenomenon described by the field of mathematics known as “chaos theory.” The butterfly effect refers to “sensitive dependence on initial conditions,” or the observation that even minute variations or fluctuations in a system can produce vastly and powerfully different outcomes at a later state. The effect gets its name from the now well-known example of a butterfly flapping its wings somewhere on the coast of South America resulting in a hurricane across the Atlantic.

The point, of course, isn’t whether or not the flapping of a butterfly’s wings, or even a preacher’s lips, can produce significant changes in weather (or behavior), but the idea that systems are deeply interconnected on levels that we can barely begin to understand. That even small changes produce significant outcomes, but most importantly that we can’t know or forecast what those outcomes will be.

This is a challenge to our hubris as human beings. Despite the fact that our knowledge of the world’s workings is constantly changing, that we are constantly replacing old ideas about how the universe works with new ones on the basis of new information, humanity generally tends to act as though it already knows all it needs to know to go traipsing off into God’s creation, crashing through the rain forests or drilling into the ocean floor, making not just small changes but massive ones at every step of the way that have created massive disruptions in the world’s climate and ecology and threatened the ecosystems for virtually every species of life on this planet, including our own.

So, the butterfly becomes a symbol of the power of something small, something frail and fragile, to effect great change in a system.

But as our preacher last week, Pastor Hector Garfias-Toledo, pointed out to us, there is a difference between knowing facts about something and having a relationship with it. In his beautiful sermon about the ocean, he reminded us that 70% of the world’s population lives just miles from the sea, and that people who live close to the sea develop a relationship with it, not just ideas about it.

The same is true for the world’s fauna, its creatures. Certainly people with pets understand the kind of bond that can emerge between human beings and domesticated animals. Farmers and hunters can have a profound respect for their inter-dependence on the breeds of animals they raise and hunt. Biologists and preservationists help us all to understand the marvel and mystery of species that exist beyond our experience, that we relate to in the most abstract manner — like the massive, 11 ton whale sharks that live in the warm equatorial seas and live off of plankton, but have become an endangered species because of the unintentional damage done to them by boat propellers.

But the truth is, we don’t even know what we don’t know about the incredibly diverse array of creatures, of fauna, of species that fill the earth.

When God speaks to Job, in response to Job’s preoccupation with his own plight, God asks,

“Who has let the wild ass go free? Who has loosed the bonds of the swift ass, to which I have given the steppe as its home, the salt land for its dwelling place? It scorns the tumult of the city; it does not hear the shouts of the driver. It ranges the mountains as its pasture, and it searches after every green thing. Is the wild ox willing to serve you? Will it spend the night at your crib? Can you tie it in the furrow with ropes, or will it harrow the valleys after you? Will you depend on it because its strength is great, and will you hand over your labor to it? Do you have faith in it that it will return and bring your grain to your threshing floor?” (Job 39:1-12, 26-30)

The Book of Job reminds us that human arrogance has imagined ourselves as the center of God’s creation since the beginning. In the invitation issued in the Garden of Eden to join God as stewards of God’s creation, we misunderstood the mandate that came with our vocation, and have treated the earth and all its creatures as if they exist solely for our benefit. Even as Job laments his own deep losses, God reminds him that creation does not exist for his benefit. The wild ass becomes emblematic of all God’s creatures who did not come into being simply to serve humanity, to be farmed, or yolked for labor.

This season of creation, which we are now celebrating for the third year in a three-year cycle, is very new. It grew out of the Lutheran Church of Australia, but has become a global, ecumenical movement that intentionally interrupts the Revised Common Lectionary we share throughout much of the Church in order to draw our attention to the urgent, unprecedented ecological crisis in which we now find ourselves. A crisis which threatens our climate, and therefore every species on earth in one form or another.

One of the features of the theological work being done by these eco-theologians has been the development of a “hermeneutic of creation,” or a way of reading scripture that attempts to dislocate humanity from the center and to recognize the subjectivity, or perspective, of all of creation. In their introduction to the preaching resource that accompanies this season, theologians Norman Habel, H. Paul Santmire, and David Rhoads, the emeritus professor of New Testament at the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago, write,

One of the features of the theological work being done by these eco-theologians has been the development of a “hermeneutic of creation,” or a way of reading scripture that attempts to dislocate humanity from the center and to recognize the subjectivity, or perspective, of all of creation. In their introduction to the preaching resource that accompanies this season, theologians Norman Habel, H. Paul Santmire, and David Rhoads, the emeritus professor of New Testament at the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago, write,

“We are seeking to read the relevant Bible texts also from the perspective of Earth and of members of the Earth community. We have become aware that in the past most interpretations of texts about creation — Earth or our kin on this planet — have been read from an anthropocentric perspective, focusing on the interests of humans. The task before us is to begin reading also from the perspective of creation.” (“The Season of Creation: A Preaching Commentary,” p. 11)

With that hermeneutic of creation in place, we are encouraged to hear even texts like Paul’s letter to the Corinthians with new ears.

“Now I appeal to you, brothers and sisters, by the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, that all of you be in agreement and that there be no divisions among you, but that you be united in the same mind and the same purpose. For it has been reported to me by Chloe’s people that there are quarrels among you, my brothers and sisters. What I mean is that each of you says, ‘I belong to Paul,’ or ‘I belong to Apollos,’ or ‘I belong to Cephas,’ or ‘I belong to Christ.’ Has Christ been divided? Was Paul crucified for you? Or were you baptized in the name of Paul?” (1 Cor. 1:10-13)

Paul is addressing himself to the problem of privilege and prejudice in the Corinthian community. Some members of the congregation have come to imagine themselves as more important, more central, perhaps even more blessed, than others because they were baptized by Paul himself. It is the basic human sin, to distance ourselves from God by distancing ourselves from one another, to harm our relationship with God by harming one another.

The hermeneutic of creation isn’t only applied to texts about wildlife, or the environment, but all of scripture. So when we re-read this passage from First Corinthians, we are encouraged to ask not only how we may be creating false distinctions between ourselves and the people sitting next to us in the pews, but also between ourselves and the species that surround us, between ourselves and the rest of creation. Do we imagine that our commissioning at the dawn of creation, the dominion God gave to the first people over Creation’s fauna, has not only set us apart from, but above, the needs of all that God has created and that God loves?

That may, indeed, be the wisdom of this world, where corporate entities consolidate our individual appetites for consumption into engines of expanding markets that treat everything like a commodity to be purchased, packaged, and sold for our pleasure. It may well be the wisdom of this world that says that environmental degradation is the necessary evil, the price that must be paid for human progress. Nevertheless, Paul speaks to us as Christians, as people saved from the powers of this world by the foolishness of the cross, the saving power of God, which makes itself known in the frail and fragile things of this world.

The cross teaches us about the folly of empire, the foolishness of placing our trust in systems of power, production and consumption that, in the end, will only enslave us, consume us, and destroy us. In fact, aren’t they already? Don’t you already sense that so much of our modern life has diminished our ability to enjoy what it means to be truly human?

Do you really think we were created for fifteen-hour work days, or weeks without sabbath? Do you really think we were created for canned vegetables and powdered potatoes when the earth is erupting with fresh fruit in its season? Do you really think that reality television and the never-ending parade of digital distractions on your smart phones and tablets are any substitute for what is actually happening in God’s reality, for the waves of Lake Michigan crashing against the lakeshore and the wild play of children and animals and sunshine and trees?

Has not God made foolish the wisdom of the world?

Jesus said to his disciples,

“Therefore I tell you, do not worry about your life, what you will eat, or about your body, what you will wear. For life is more than food, and the body about more than clothing … And do not keep striving for what you are to eat and what you are to drink, and do not keep worrying. For it is the nations of the world that strive after these things, and your Father knows that you need them. Instead, strive for his kingdom, and these things will be given to you as well.” (Luke 12:22-23,29-31)

Sounds like foolishness, doesn’t it? How are we to stop worrying about our lives, our next meal, our shelter and our clothing? Still, there is wisdom in this foolishness. Imagine the sabbath the earth and all its creatures would experience if we could curb our unceasing appetites and live lighter upon the earth.

Consider the beautiful monarch butterfly, another of Creation’s endangered species. It neither buys nor sells, but through the innate wisdom implanted in it by God its creator, it migrates unimaginable distances from the United States to Mexico each year, traversing national boundaries to make its home among people divided by wealth, ethnicity, language and power. Consider the monarch butterfly, in its frail, fragile beauty, which enters the tomb of its cocoon as a caterpillar and emerges ready to flutter, to fly, to become more than it had ever been. If God so equips the monarch butterfly for its future, how can we imagine God in her infinite compassion, would do anything less for us?

Consider the beautiful monarch butterfly, another of Creation’s endangered species. It neither buys nor sells, but through the innate wisdom implanted in it by God its creator, it migrates unimaginable distances from the United States to Mexico each year, traversing national boundaries to make its home among people divided by wealth, ethnicity, language and power. Consider the monarch butterfly, in its frail, fragile beauty, which enters the tomb of its cocoon as a caterpillar and emerges ready to flutter, to fly, to become more than it had ever been. If God so equips the monarch butterfly for its future, how can we imagine God in her infinite compassion, would do anything less for us?

Amen.