Texts: Hosea 1:2-10 + Psalm 85 + Colossians 2:6-15 + Luke 11:1-13

Preaching last week on God’s wrath, I named a couple of ways that most of us dodge the discomfort of dealing with divine anger — by defending ourselves as mostly good, or by declaring that most of us (though not all) are good. My assertion was that both of these dodges keep us from recognizing the power of anger in the work of love.

Well, I have to confess to you, my sisters and brothers, that I’ve been trying to dodge all week long as I prepared for this week’s installment of the “School for Prophets.” All summer long we’ve been reading and studying the oft-neglected prophetic books from Hebrew scripture, the books that form the backbone of Jewish and Christian ethical reflection on the world, and in their call for personal righteousness and political reform we have heard a good word for our day. But today we move into two weeks with the prophet Hosea, and his language and imagery are so difficult to read, much less to preach on, that I really wanted to dodge the bullet and go back to preaching on the gospels.

This week the gospel of Luke presents Jesus teaching the Lord’s Prayer. While the spirituality of that prayer is certainly radical in its call for simplicity, forgiveness of debts, and reliance on God; the language is so familiar that it barely registers with us anymore as anything other than a word formula to be recited from memory.

The language of Hosea, on the other hand, is shocking. So shocking that, in the end, after looking at about five different translations, I ended up softening the language of the text we heard Bob read a few minutes ago out of fear that we’d lose half the room after the first two verses.

The actual, commonly accepted, translation of these verses begins,

When the Lord first spoke through Hosea, the Lord said to Hosea, “Go, take for yourself a wife of whoredom and have children of whoredom, for the land commits great whoredom by forsaking the Lord. (Hosea 1:2, NRSV)

You can see why I might be tempted to just focus on the Lord’s Prayer.

This ends up being, really, the dominant motif of the prophet Hosea, that Israel has prostituted itself out to foreign nations and other gods. That Israel has broken the covenant between itself and Yahweh by placing its trust in other powers to give and sustain life. And as I tried to think about how to preach the prophet Hosea with integrity, the real temptation (other than to simply not preach Hosea) was to excuse the prophet’s misogyny and explain away the rhetoric of violence against women that follows the verses we read this morning. I wanted to mount a biblical “It Gets Better” campaign by skipping ahead to the brief, rare verses in Hosea that promise reconciliation with God and a new future for the people of Israel.

But to do that, to read these verses out loud in the sanctuary and let the words “whoredom” and “prostitute” ring off the walls of the church, and then skip ahead to some other passage in order to escape the ugliness and cruelty of those words is another kind of dodge that, in the end, does not produce faith but instead sows doubt — doubt that these scriptures are actually trustworthy after all, doubt that we can read and wrestle with difficult texts and come out the other side stronger for having done so.

In her groundbreaking book, “Texts of Terror: Literary – Feminist Readings of Biblical Narratives,” biblical scholar Phyllis Trible explores the problem of violence in scripture, particularly the all-too-common violence against women found in scripture. She names the dodges we too often take in our approach to the problem of violence like this:

From the start, certain theological positions constitute pitfalls. They center in Christian chauvinism. First, to account for these stories as relics of a distant, primitive, and inferior past is invalid. Resoundingly, the evidence of history refutes all claims to the superiority of a Christian era.

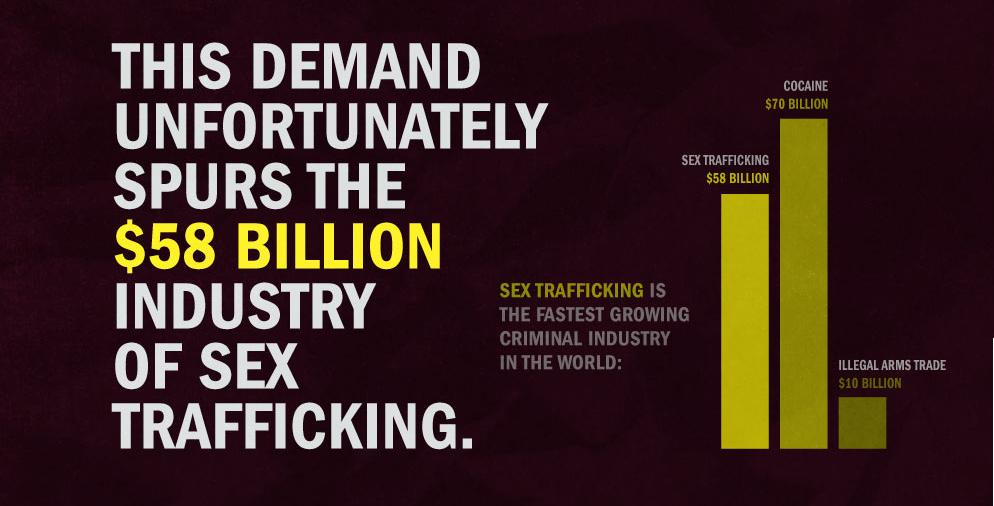

Trible already catches me, red-handed, in the act of trying to dodge the problem of the prophet Hosea by explaining his use of misogynistic language like “whoredom” and “prostitute” as if those words are somehow a relic of the past that I would need to explain to you in the context of biblical history; as if they aren’t thrown at women (and men) everyday as insults and forms of social control; as if prostitution isn’t a global industry that creates wealth for men at deep and devastating cost to women. No, we can’t escape the problem of the prophet Hosea by pretending as if his rhetorical violence is a relic of a biblical past, when we know that it is an all-too-common fact of the present as well.

Trible continues,

Second, to contrast an Old Testament God of wrath with a New Testament God of love is fallacious. The God of Israel is the God of Jesus, and in both testaments resides tension between divine wrath and divine love.

This is also a move we Christians too often make, to the detriment of our own faith and at the expense of our Jewish sisters and brothers as well. There is a subtle anti-Judaism that creeps into Christian language when we contrast what we call the Old Testament, which is Hebrew scripture, with the New Testament, as if Christians really only need the later, not the former. As if the Jesus we meet in the second testament, and the authors who are presenting him, are not quoting frequently and directly from the first testament.

We must learn to say plainly that it simply is not true that the God of the Old Testament is a God of wrath, while the God of the New Testament is a God of love. God acts again and again in Hebrew scripture, moved by love, to create, save and restore God’s people and God’s creation. Likewise, the New Testament is filled with language — in the gospels, in Paul’s letters, and elsewhere — that affirms the power of anger in the work of love. So, no, we cannot dismiss Hosea’s angry, violent language toward his wife and children as “typical” of Hebrew scripture. If it is typical, it is of something far more universal and encompassing than any one religious tradition.

If we cannot pretend that the issue of violence against women is limited to the ancient past, and we cannot dismiss these verses as diminished Old Testament precursors to a new-and-improved Christian Testament, then how are we to read these passages? How are we to read the bible as a whole?

Phyllis Trible makes this suggestion:

Offsetting these pitfalls are guides for telling and hearing the tales. To perceive the Bible as a mirror is one such sign. If art imitates life, scripture likewise reflects it in both holiness and horror. Reflections themselves neither mandate nor manufacture change; yet by enabling insight, they may inspire repentance. In other words, sad stories may yield new beginnings.

Honesty and integrity demand that we not gloss over the violence of Hosea’s rhetoric. We can neither read his message to the nation of Israel, “for the land commits great whoredom by forsaking the Lord,” as a relic of the past, nor can we gloss over it and pretend it is not a feature of our own present-day society.

Instead, let’s do this. Let’s affirm that the women and children, both female and male, used in prostitution are entirely human, equally created in the image of God, deserving of love and compassion, and worthy of respect. Let’s not pretend that prostitution is something that only happens to people we don’t know, or is engaged in by people we don’t know. Given how prevalent it is in our own city, that is simply too unlikely to be true.

What that means in very practical terms is this: in this house, in this church, you are always welcome. This does not stop being true if you have been prostituted. This does not stop being true if you are currently engaged in prostitution. Those are facts that cannot define a person. Our deepest reality is that we are, each of us, created in the image of a loving God who unrelentingly searches us out so that we can be healed and restored to right relationship with God and with one another.

So I think one of the gifts that can be wrangled out of these explosive verses from Hosea is this: they force us to say words we’ve been taught not to say in polite company. They hold a mirror up to our society, and they demand that we be clear that the good news of God’s justice-making love is intended for everyone, and by putting us on the record they also insist that we act in ways that make this affirmation true. I know that, this past Christmas, our social justice committee hosted a holiday shopping party at which all the items being sold supported the work of a Christian ministry advocating for an end to human sex-trafficking. I’ve been encouraged to see that the Evangelical church in particular has been active in working to shed light on this problem, and to support women and children who are able to leave prostitution and build new futures for themselves and their families.

There is another fact, however, that faces us in the mirror that scripture holds up to us in the words of the prophet Hosea. I’ve struggled with how to say this, and I’m not entirely sure I’m going to get it right, so I just want to ask for your patience with me as I try to say something I see in these scriptures in the best way I know how, entirely aware that I likely won’t get this right.

As horribly intimate as Hosea is with his imagery — a wife used in prostitution, three children who he names “Jezreel” as a sign of punishment, “Lo-ruhamah” meaning “No Pity,” and “Lo-Ammi” meaning “Not My People” — he is trying to communicate something to the entire nation about their conduct as a people. He uses his own marriage to a wife who has been prostituted to describe the state of affairs in the relationship between God and Israel, and to his way of thinking God is like a faithful spouse who endures humiliation after humiliation at the hands of a faithless partner. I’m stripping the genders away from the metaphor, which I understand is a problem since the symbol is so rooted in patriarchy and power, but I’m trying, very imperfectly, to get at what I think Hosea was trying to get at, very imperfectly; and that is that when we talk about politics in church, we’re not talking about some impersonal set of ideas or laws or trade practices — we’re talking about ways of structuring our life together as a community that have deep and profound impact on all of us, as individuals and families, as neighborhoods and nations.

As you read through the entire fourteen chapters of Hosea you discover that what he’s really angry about is the way that Israel has misplaced their trust in the very powers that have previously enslaved them. He writes, “they call upon Egypt, they go to Assyria,” (Hos. 7:11b) and goes on to say,

You have plowed wickedness, you have reaped injustice, you have eaten the fruit of lies. Because you have trusted in your power and in the multitude of your warriors, therefore the tumult of war shall rise against your people, and all your fortresses shall be destroyed. (Hos. 10:13-14)

Hosea accuses Israel of being faithless, of abandoning their covenant with God, of seeking power and pleasure from the hands of the very people and places that have always been the source of their oppression. He indicts them of placing their trust in their military, of using war as a method for getting what they want at the expense of others.

Doesn’t this all sound a little bit too familiar? Don’t we sense that sometimes our own culture, our own society, keeps turning again and again to powers that we know are broken, systems that we know are hurting us, but which we have decided are “too big to fail.” Can we imagine that as these systems rob us of our homes and our jobs, as these forces commit us to war after war so that we can maintain control over resources that rightly belong to all God’s people, that God’s wrath — which is God’s anger directed toward the work of love — might be kindled?

The image that Hosea reaches for, the symbol he uses to try and help Israel understand that talking about politics in church is actually talking about the very things that affect us in our homes on a day to day basis, is a symbol of domestic violence. He uses language that demeans and denigrates his wife and his children, and he goes on to describe the ways they will be punished for their faithlessness that would, and should, get him arrested if he tried them today.

I am not excusing that, but I am trying to understand the message he is trying to deliver as he speaks in such graphic terms on behalf of God to the nation of Israel. Here is my best attempt to boil that message down to something that does not harm or objectify women and children:

Oh my people, when will you learn that the personal is political and the political is personal? When will you understand that your chasing after dreams and illusions of pleasure and privilege always come at the expense of someone else, the expense of the very land we rely upon for life? When will you start living as if the promises we made to one another in baptism mean something to you, and not just to me? When will you finally treat me, and one another, with the love I have always given to you?

Hosea uses the language of marriage and infidelity, I think, because it is some of the most powerful language we have available to us. If you have ever had to talk with your lover, your partner, your spouse about infidelity, then you know how scary and painful and explosive those conversations can be. Hosea draws on those emotions, and our almost universal experience with those emotions, to try and help us understand on a visceral level what is at stake in our relationship with God, not just at home in our private religious lives, but out in the world, in public, in our collective lives.

In many ways, he fails. His inability to really even see the violence he perpetrates against his wife and children as he tries to make his point to the nation of Israel is a reminder to us all that we must guard against self-righteousness. Still, I’m glad that our tradition has kept Hosea in the Bible. His personal failures teach us something about the frailty of our own best efforts, while still demanding that we all be honest about our collective failures before God.

Amen.