Texts: Daniel 7:9-10, 13-14 and Psalm 93 • Revelation 1:4b-8 • John 18:33-37

Grace and the peace that passes all understanding be with you, my brothers and sisters, in the name of Christ our King. Amen.

As we gather at the end of this Thanksgiving weekend — days filled, for many of us, with travel to see family and friends; tables filled with extravagant food and drink as a reminder of the abundance with which we are blessed, even in these trying financial times — I am feeling truly thankful for events taking place far from Chicago. When we gathered a week ago for worship, we were praying for peace in Gaza. The following day a handful of us took part in a peace rally downtown that drew thousands of people here in Chicago as similar events took place around the world. On Wednesday, as families in the United States prepared to take stock of their lives and give thanks for their many blessings, a ceasefire was negotiated between the nation of Israel and the leaders of Hamas, the party in power in Gaza. After seven days of fighting, two hundred Israelis and Palestinians were dead and over a thousand had been wounded. While the ceasefire is holding for now, a more lasting peace is still far off on the horizon.

The conflicts in Israel and the Palestinian territories are being fought on lands that have seen the rise and fall of the most ancient of nations, the first being the Mesopotamians who inhabited what is now called Iraq. The Mesopotamian empires gave us cuneiform, the first form of writing. They were amazingly complex politically, religiously, socially. Now they are gone.

The Mesopotamian empires passed officially into history when they were conquered by Alexander the Great as part of his crusade to conquer the world. This began what historians call the Hellenistic Age, which lasted until 31 BCE when the Egyptians were defeated by the Romans at the Battle of Actium, prompting their queen, Cleopatra, to commit suicide – famously re-enacted 2000 years later by Elizabeth Taylor.

The Mesopotamian empires passed officially into history when they were conquered by Alexander the Great as part of his crusade to conquer the world. This began what historians call the Hellenistic Age, which lasted until 31 BCE when the Egyptians were defeated by the Romans at the Battle of Actium, prompting their queen, Cleopatra, to commit suicide – famously re-enacted 2000 years later by Elizabeth Taylor.

The Roman Empire should be more familiar to us, since it serves as the backdrop to the gospels and the life of the early church. When we hear the stories of Caesar Augustus and King Herod, we are hearing tales from the Roman Empire. It was hostile to the early church, and was the cause of many Christian martyrs… until the Emperor Constantine, who in the fourth century made Christianity the religion of the Empire. That was reputedly good for the Christians, but didn’t do much for the Roman Empire, which fell about 100 years later to Germanic invaders.

I could go on and tell you all about the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, which held together for the most part for three hundred years of so. Somewhere in there you’d hear the story of a scuffle in which a monk named Luther played a bit of a part, leading to a deterioration of the Empire and the formation of smaller nations: Austria, Prussia and the like. That left room for the rise of the British Empire, which prided itself on being the most extensive empire in the history of the world, boasting that the sun never set on its lands. By the early years of the twentieth century the British empire counted over 450 million people in its territories and holdings.

The wars of the twentieth century brought that empire to a close however, and began what TIME/LIFE publisher Henry Luce called “The American Century.” Historians mark the American Century as beginning with the Spanish-American war and reaching its peak during the fever pitch of the Cold War during the 1980s. From 2003 until just about this time last year the United States had troops on the ground back in Mesopotamia – or Iraq. The costs of that war, along with the one in Afghanistan, has left our country with tremendous debt and has eroded our ability to maintain and expand the social infrastructure that creates growth and prosperity – which has prompted many around the world to remark that the American Century is now over.

So many beginnings and so many endings, and each time the same story: empires built on the spoils of war, empires crushed by failure at war, empires called into being and replaced, over and over again. Where do we suppose it will end?

When you tell the story of our human history, when you hear the bloody tale of nations and wars, it is enough to make you run for cover. In the face of the stormclouds of war, we wonder if there are boats sturdy enough to carry us through the storm and safely to the far shore. In a world of violence we naturally look for sanctuary.

Well friends, we need not look far. This sanctuary in which we sit is both safe refuge and sturdy transport. In fact, and I’m sure you know this already, but the area in which you are sitting – what we call the nave – get its name from marine terminology. Can you hear the similarity between the words: nave, navy, naval? The intent, when our mothers and fathers in the faith named their worship spaces, was that we would remember that God has acted to provide safe refuge from the destructions of life. Like Noah’s ark that carried a remnant safely across “the thunders of mighty waters” [Ps. 93:4], this sanctuary is God’s gift to us as we make our way in a violent world.

Well friends, we need not look far. This sanctuary in which we sit is both safe refuge and sturdy transport. In fact, and I’m sure you know this already, but the area in which you are sitting – what we call the nave – get its name from marine terminology. Can you hear the similarity between the words: nave, navy, naval? The intent, when our mothers and fathers in the faith named their worship spaces, was that we would remember that God has acted to provide safe refuge from the destructions of life. Like Noah’s ark that carried a remnant safely across “the thunders of mighty waters” [Ps. 93:4], this sanctuary is God’s gift to us as we make our way in a violent world.

Later this morning we’ll hear from Lyn Westman who works with Mercy Ships, an international Christian ministry that brings medical aid and assistance to some of the poorest people and nations in the world — a ministry that takes the shape of this sanctuary quite literally.

But it doesn’t end there, because this sanctuary is not only the boat that carries us across the waters, it is also the far shore to which we are headed. You see, it appears that God has something far more grand in store for us than sheltering us from the wars of one world, only to drop us in the conflicts of whichever empire is coming next. No, instead God has lifted us out of not just one nation, but every nation, and made of us an entirely new people. You heard it in the reading from Revelation, “to [God] who loves us and freed us… and made us to be a kingdom.”

This is very difficult to imagine, that God is lifting us out of our many and varied backgrounds and creating something new, a new body, a new family, a new kingdom, a new nation. It’s something so new, that we struggle even to find good words or symbols that can teach us the meaning of what God is doing. But we try.

Let’s imagine then that this sanctuary in which we gather is not only a nave, not only a ship, but that it has, and does and will carry us into a new way of being in the world. Let’s imagine together what it might be like to disembark from this ship and enter into this new land on these imagined shores. It’s as though we’ve arrived at Ellis Island, having left the old country behind us – except the nation that we are about to step foot in is not the United States. It is, as Jesus speaks it to Pilate in today’s gospel a kingdom “not from this world.” Something brand new, difficult to imagine, but for which we have been given signs.

Let’s imagine then that this sanctuary in which we gather is not only a nave, not only a ship, but that it has, and does and will carry us into a new way of being in the world. Let’s imagine together what it might be like to disembark from this ship and enter into this new land on these imagined shores. It’s as though we’ve arrived at Ellis Island, having left the old country behind us – except the nation that we are about to step foot in is not the United States. It is, as Jesus speaks it to Pilate in today’s gospel a kingdom “not from this world.” Something brand new, difficult to imagine, but for which we have been given signs.

So if this were an Ellis Island experience, the first thing we would have to worry about is immigration. Having weathered the storms of life, of war and of death, we might wonder whether or not we would even be granted access to this new and promised land. What might we look to in the sanctuary to teach us about the immigration policy in God’s new nation?

We HAVE been given a sign and a sacrament to teach us something about who is welcome in this kingdom, and it is baptism. These waters marked entrance into the kingdom for each of us. These waters, the tears of God, are an open door for everyone. We wash babies and we wash the aged and dying in these waters, and in both cases the water is a gift, not a right or an entitlement. This is the immigration policy in God’s new nation: come one and come all, there is plenty of room.

Now that we have entered into this new land we are refugees and immigrants. So, like all refugees and immigrants we have some very basic necessities that we must attend to: what will we eat and how will we support ourselves? We might be concerned, seeing how immigrants in those nations we have left behind us were often made to fend for themselves, but soon we discover that there is a new kind of economic policy in the kingdom of God. Here there is a table filled with rich foods and life-giving wine, and even better, there is room at the table for everyone. However much we may eat at this table, there is some left over. Even better, we are given legitimate employment right away, as we discover that our job now is to share the food and the blessings of this table with those who are still hungry for the gifts of God!

Now that is no easy task. If fact, it is a job that could consume all our time, yet we make time in this new nation to return for basic citizenship classes. As I understand it, when people arrive in the United States we require about 16 hours of instruction before you sit for the test that determines whether or not you get your green card or your naturalization papers. We teach you basic history, the Constitution, the pledge of allegiance. But what about the new nation? Here we do NOT sit for a test. I suppose we have a Constitution of sorts, but it is a much grander one – it is the Word of Life, read aloud among the people and then proclaimed from the pulpit. It is not fixed in time, but instead it is a living Word that constantly rises to reveal the truth of our lives to us. It is Scripture, surely, but more than that it is our living Lord, Jesus, who “came into the world to testify to the truth.” We have basic history lessons that we learn, they are our creeds, they are our way of remembering the story of those who came before us in faith, who made their witness to the world about the freedom of life in the new nation. We have our pledge of allegiance, but we call it the Lord’s Prayer, and instead of talking about ourselves and our promises, we use our prayer to recall to one another who God is: the one who creates, the one who saves us from the time of trial, the one has made us into one body, one family, one kingdom, one nation, one new thing for which we are still looking for words.

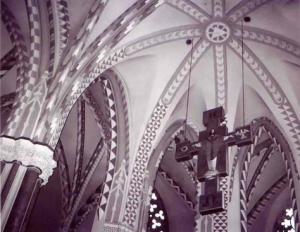

Look around the sanctuary friends, it is filled with familiar signs each of which is actually a clue to the kind of king Christ seeks to be in the world and in our lives. We even have a flag! Where do you suppose we place it?

Why front and center, of course. It hangs above our altar. Do you see our flag? It is the cross of Christ – the evidence of God with us throughout all the wars, all the violence, all the deaths in our lives, great and small, and transformed into life by the God who does not leave us ever, and who gives us to one another, across lines of race and nationality, across lines of hatred and hostility, and says: you are now family to one another, you are my family.

Why front and center, of course. It hangs above our altar. Do you see our flag? It is the cross of Christ – the evidence of God with us throughout all the wars, all the violence, all the deaths in our lives, great and small, and transformed into life by the God who does not leave us ever, and who gives us to one another, across lines of race and nationality, across lines of hatred and hostility, and says: you are now family to one another, you are my family.

Our lessons this morning describe for us an awareness of God’s kingdom that is always with us. Daniel remembers that “all peoples, nations, and languages should serve [God].” [Dan. 7:14] John of Patmos, speaking in that strange apocalyptic language says, “every eye will see him, even those who pierced him; and on his account all the tribes of earth will wail.” [Rev. 1:7] Wail because we someday, surely, will finally come to know what has always been true: that it is God who is the Alpha and Omega [Rev. 1:8], the beginning and the end. The nation that has always existed and will never fail.

We would like to think that we are citizens of a nation that can never fall, but that is not so. We are not, in the end, too very different from the Mesopotamians, or the Greeks, or the Romans, or the Germans, or the English. For that matter, we’re not that very different from the Mongols who created the largest land empire, spanning all of Asia; or the Aztecs, whose society collapsed from the inside as a result of their decadent and conspicuous consumption of the land’s resources. We are always trying to have it both ways, dual-citizenship if you will. “For God and Country,” or “pro deo et patria” – ironically, that is the slogan of the Army chaplains. They who have been called to stand in the midst of war and to be a sign that God is present, even there.

Of course God is present everywhere, in every people, and always has been. When we gather here, in this place, this sanctuary, let us remember that this is not only refuge from the storm – but also conveyance to the new country. Let us be very intentional about the words and signs and symbols that we use in this place so that we are not simply pointing to the broken and fading realities of the present age, but instead to the in-breaking and glorious realities of the world that is to come, and that is now drawing close in Christ, our King.

Amen.