Texts: Isaiah 65:17-25 + Psalm 48:1-11 + Romans 8:28-39 + Mark 16:14-18

In the name of Jesus, our mountain, our Zion.

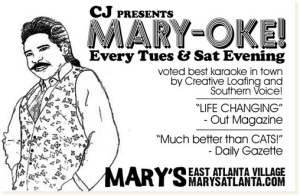

Back when I was in seminary, there was a bar in East Atlanta that we seminarians liked to haunt named Mary’s. Mary’s hosted karaoke on Thursday nights, and the Master of Ceremonies was this very short, dark-skinned man named C.J. who always kicked the night off with something by Diana Ross or the Supremes. His standard was “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough,” and when he sang that song, you thought Ms. Ross herself was in the house.

Back when I was in seminary, there was a bar in East Atlanta that we seminarians liked to haunt named Mary’s. Mary’s hosted karaoke on Thursday nights, and the Master of Ceremonies was this very short, dark-skinned man named C.J. who always kicked the night off with something by Diana Ross or the Supremes. His standard was “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough,” and when he sang that song, you thought Ms. Ross herself was in the house.

Looking back, I’m surprised that none of us bright seminarians ever made the connection between the lyrics to that song and the text from Paul’s letter to the Romans that we heard this morning. Paul writes, “For I am convinced that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor rulers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord.” Diana Ross shortened the list and cut to the chase, singing in God’s own voice, “ain’t no mountain high enough, ain’t no valley low enough, ain’t no river wide enough to keep me from getting to you!”

There’s an element of poetry to both Paul’s and Diana’s exclamations. We don’t really imagine God coming down off the mountain to claim us any more than we imagine Diana Ross wading across the Mississippi River to get to her lover. But the mountain and its peaks has held a place in the collective mythology of humanity from our very beginnings. The ancient Greeks imagined their gods ruling and residing atop Mount Olympus. The ancient Israelites imagined God to reside atop Mount Zion, and expected that it would be from there that God would act to protect God’s people. Later, when they’d been taken into exile, prophets like Isaiah and those who later wrote in his voice imagined God’s restoration pouring forth from Mount Zion, as if it were the epicenter of wave of divine energy that would finally cover the whole creation making all things new.

It’s not hard to understand why the ancient religious imagination associated mountains and their peaks with God’s presence. When you stand at the base of a mountain, or live in the shadows of its valleys, mountaintops seem to touch the skies from which life-giving waters fall. Mountaintops, sometimes covered in clouds, seem to be the source of the thunderclaps and lightening bolts that accompany the power of the storm. Climbing a mountain was hard work, and the rewarding views awaiting those who could make the climb made an easy analogy for the life of faith.

Throughout the history of Israel there were disputes about which mountaintops were the appropriate site for offering sacrifices to God. King David built his city, Jerusalem, near Mount Zion and Solomon established the temple there. Centuries later, when Jerusalem came under Roman occupation, mountains were a source of tension between Jews and Samaritans. You’ll remember that Jesus, in his conversation with the Samaritan woman at the well, is told “Our fathers worshipped on this mountain (a reference to Mount Gerazim), but you Jews claim that the place where we must worship is in Jerusalem.” (John 4:20)

Jesus’ reply to the Samaritan woman signals an important shift that was taking place in the first century, as Jews and the early Christians responded to Rome’s destruction of the Temple. Jesus says,

“Believe me, woman, a time is coming when you will worship the Father neither on this mountain nor in Jerusalem. You Samaritans worship what you do not know; we worship what we do know, for salvation is from the Jews. Yet a time is coming and has now come when the true worshippers will worship the Father in spirit and truth, for they are the worshippers the Father seeks. God is spirit, and his worshippers must worship in spirit and truth.” (John 4:21-24)

Under imperial occupation, the mountain temple associated with God’s holy presence was destroyed, an event that effectively cut off the Jewish people from their religious practices and forced an amazing evolution in religious identity, leading to the development of what we would now call rabbinic Judaism.

At the same time, Christianity was being born, and the teacher Jesus became the resting place for much of the mythic freight previously lain on the mountain Temple. Where once the faithful had ascended the mountain to offer praise and worship at the Temple in Jerusalem, the bridge between heaven and earth, now Jesus came to them — fully human and fully divine.

Matthew’s gospel, in particular, goes to great lengths to give us images of Jesus as the new mountaintop experience: Jesus experiences temptation on a mountain (Mt. 4:8-10); Jesus delivers the body of his teaching on a mountain (Mt. 5:1 — 8:1); Jesus feeds the multitudes on a mountain (Mt. 15:29-31); Jesus is transfigured on a mountain (Mt. 17:1-9); and the risen Jesus — in a scene that seems to have inspired the addendum to Mark’s gospel that we read this morning — commissions those who’d followed him from to go out into the world, making disciples of all nations (Mt. 28:16-20).

The early church picked up on these images of the mountaintop Jesus, acting as the cosmic bridge between heaven and earth, and incorporated them into its religious art. To this day, if you walk into some Orthodox and Roman sanctuaries and look up, you will see an image on the ceiling of the risen Christ ruling from heaven. In essence the church built its own mountaintop retreats, inviting us all to come in and encounter the God who met Moses on the mountaintop once again in the person of Jesus.

The early church picked up on these images of the mountaintop Jesus, acting as the cosmic bridge between heaven and earth, and incorporated them into its religious art. To this day, if you walk into some Orthodox and Roman sanctuaries and look up, you will see an image on the ceiling of the risen Christ ruling from heaven. In essence the church built its own mountaintop retreats, inviting us all to come in and encounter the God who met Moses on the mountaintop once again in the person of Jesus.

Even Protestant churches, ambivalent as we’ve been to icons in our worship spaces, have continued to raise up steeples like mountains and top them with crosses. The function is the same, to elevate an image of the presence of God over our sanctuaries as a sign that God meets us here, at the cross, the bridge between heaven and earth.

Perhaps it is because we have, in our religious imaginations, removed God from the mountaintops and relocated God into our sanctuaries, that we no longer care so deeply for the real-life mountaintops here at home and around the world. Sure, on an individual basis, we may still choose to vacation in the mountains so that we can hike or ski, but outside the resorts of Colorado and northern California, the mountains where our Native predecessors worshipped, the mountains so adored by Henry David Thoreau and John Muir, are being destroyed.

If you haven’t heard of Mountaintop Removal Mining (MRM), I highly recommend to you a documentary that came out last year, directed by Bill Haney, called “The Last Mountain,” which examines the impact of coal mining on our lands, our health and our culture. The film centers on the battle to keep Coal River Mountain in West Virginia from being blown apart for coal — a process that, until very recently, was illegal under the Clean Water Act of 1972.

Mountaintop coal mining, which accounts for only about 5% of coal production in the United States, but almost 30% in areas like West Virginia, “has destroyed 500 Appalachian mountains; has decimated 1 million acres of forest; has buried 2,000 miles of streams and is contaminating thousands of miles more.”

The process of stripping coal from the mountaintops involves, first, stripping each of these mountains of the native forests that have grown there over centuries; then, literally blasting the tops off the mountains with 25 tons of explosives each day, a weekly total equivalent in force to the bomb dropped in Hiroshima, in order to expose the veins of coal.

Instead of radioactive fallout, this process releases coal dust and silica into the air, which coats surrounding communities. In one small West Virginia town, six children and adults living within a few blocks of one another developed brain tumors, which typically occur in one out of every 100,000 people. Most died.

Because mountaintop removal takes place near the headstreams that water much of America, the lead, arsenic, selenium and other metals released by this process have made their way into the water supply hundreds of miles away, increasing the risk of cancer.

Even we, here in Chicago, over 500 miles from West Virginia experience the impact of coal mining, as the coal shipped from sites like the ones in the Appalachians makes its way to coal-fired power plants like the Fisk and Crawford plants located in the Pilsen and Little Village neighborhoods. According to the group Chicago Physicians for Social Responsibility, these two plants alone annually emit over a quarter of a million pounds of particulate matter into the air, almost 18,000 tons of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxide; and 269 pounds of toxic mercury. These emissions are major contributors to the elevated incidence of asthma in these communities and have been linked to 41 premature deaths, 550 additional emergency room visits, and 2,800 additional asthma attacks each year.

In addition to measuring and reporting on the problem, Chicago Physicians for Social Responsibility acted in partnership with more than 60 other organizations, including the Catholic 8th Day Center for Justice, Protestants for the Common Good, SOUL (a coalition of congregations on the south side of Chicago), and Faith in Place — the interfaith environmental advocacy organization we supported with our justice offering at the beginning of this month, and whose first offices were here at St. Luke’s almost a decade ago. Working together as the Chicago Clean Power Coalition, these activists — faith-based and others — succeeded in getting Midwest Generation, the parent company to these two coal-fired power plants, to shut down. The Fisk plant in Pilsen shuts down this year, the Crawford plant in Little Village will shut down by 2014.

These victories, small in the scope of the global struggle for clean energy but significant when measured by the lives they will save, call to mind the vision for the new creation voiced in our reading from Isaiah this morning. Too often we read the prophesy of a new heaven and a new earth as a forecast of some heavenly future waiting for us after this life, beyond this world. Nothing could be further from the truth. The prophet was writing to a people who’d experienced exile, who’d been forced off their land by multinational powers spreading across the ancient near east and gobbling up the land’s resources. The people this prophet wrote to console weren’t longing for an afterlife, they were longing to be restored in this life. So, to them, the prophet writes, “no more shall there be in it an infant that lives but a few days, or an old person who does not live out a lifetime… they shall not hurt or destroy on all my holy mountain.” (Isa. 65:20, 25b)

Even the author of the postscript to Mark’s gospel, with its imagery of snake handling and exorcisms that is so foreign to us, is clearly talking about a power at work in us for the healing and liberation of this world and not the next. Hear again, in the context of our concern for the toxins released by mountaintop removal, as Jesus says, “and if they drink any deadly thing, it will not hurt them; they will lay their hands on the sick, and they will recover.” (Mk. 16:18)

Friends, we may not have the sort of miracle working faith that can withstand a snakebite, but we have seen, here in our own city, the miracle of faith that happens when people of goodwill and courage act together to serve the interests of those most vulnerable among us, when we stand together with God’s creation and not against it. Change does happen. Plants are shut down. We are a new creation.

But the powers and principalities against which we labor are not so easily defined as big coal, though they certainly have their part in this drama. Almost half of the electricity in the United States comes from burning coal. That equals 16 pounds of coal are burned each day for every man, woman and child in the United States, and one-third of that coal comes from Appalachia.

Big coal isn’t simply the problem, they are a provider of a resource, electricity, that we have come to take for granted. Until we stop to examine where this resource comes from, how it gets to the outlets that power our home appliances and warm our homes, and whose communities are most negatively impacted by this process — we won’t understand the part that each of us plays in both the destruction and the restoration of God’s creation, which is being made new each day.

For this reason, I really hope that as many of you as possible will mark Sunday, October 7 on your calendars. That’s the day, two weeks from today, that we’ll be screening the documentary “Gasland” here at St. Luke’s. That film explores another controversial method for extracting fuel for electricity from the earth, hydraulic “fracking,” and will serve as a good coda to this year’s Season of Creation.

Living on the plains of the Midwest, along the shores of Lake Michigan, we may imagine ourselves removed from the province of the mountains. We do, however, have the John Hancock building and the Willis Tower (which I still can’t stop calling Sears Tower), the place where our city touches the sky. And here in the church, we still have our steeples and our crosses. Ancient Israel imagined that God’s restoring power would begin at God’s holy mountain, Mount Zion, and would sweep across the face of the earth — that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor rulers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation — would be able to prevent God from claiming us and reclaiming us. Inspired by the power of the Holy Spirit, that blows across the face of the earth like wind over the wind farms that are spreading across Illinois and the central plains states, providing a new, clean source of power for communities not far from here, let us pray that we — acting in concert with others — might be a center for God’s healing power to roll down from and for the mountains.

Living on the plains of the Midwest, along the shores of Lake Michigan, we may imagine ourselves removed from the province of the mountains. We do, however, have the John Hancock building and the Willis Tower (which I still can’t stop calling Sears Tower), the place where our city touches the sky. And here in the church, we still have our steeples and our crosses. Ancient Israel imagined that God’s restoring power would begin at God’s holy mountain, Mount Zion, and would sweep across the face of the earth — that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor rulers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation — would be able to prevent God from claiming us and reclaiming us. Inspired by the power of the Holy Spirit, that blows across the face of the earth like wind over the wind farms that are spreading across Illinois and the central plains states, providing a new, clean source of power for communities not far from here, let us pray that we — acting in concert with others — might be a center for God’s healing power to roll down from and for the mountains.

In the name of Jesus, our mountain, our Zion. Amen.