Texts: Acts 10:34-43 • Psalm 118:1-2, 14-24 • 1 Corinthians 15:1-11 • Mark 16:1-8

Christ is risen. Alleluia!

Christ is risen, indeed. Alleluia!

“You are looking for Jesus of Nazareth, who was crucified. He has been raised; he is not here.”

What a message to proclaim on the Sunday morning when we’re most likely to have new faces in our worship service! “You are looking for Jesus of Nazareth, who was crucified. He has been raised; he is not here.” Whatever you came here this morning to find, it’s not here.

Oh, I suppose that’s not necessarily true. I suppose for some people, perhaps most people, coming to church on Easter morning is a way of digging up something from their past, dusting it off, checking it out to see how time has treated it, seeing if it still holds the luster of childhood memories. A bit of ritual. A nod to tradition. A way to keep family happy. Certainly not much talk of Jesus of Nazareth, a teacher, a healer, a prophet, a child of God, a crucified convict. Folks hope that by Easter morning we’re done talking about that part.

But we’re not. We’re not done talking about that part. In fact, that’s the part we’ve been talking about for the last two-thousand years, and that’s the part that makes us who we are, that gives us our name — Christians. A Christian is someone who makes a faith statement about who the human being on the cross was. We say he was Christ, we say he is Christ. Christ, which means “the anointed one” — the one chosen to do God’s work. That term, anointed, literally means to be covered with oil — the “oint” in “anoint” being the same root that is found in words like “ointment.”

Saying that Jesus is the one chosen, anointed, to do God’s work has been the essence of Christian proclamation from the first generation on. Paul writes to the Corinthians,

Now I would remind you, brothers and sisters, of the good news that I proclaimed to you, which you in turn received, in which you also stand, through which also you are being saved, if you hold firmly to the message that I proclaimed to you — unless you have come to believe in vain. For I handed on to you as of first importance what I in turn had received: that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures, and that he was buried, and that he appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve.

Christ died for our sins, in accordance with the scriptures, and then he was buried. But then something happened. He appeared to Cephas, also known as Simon Peter, the one who denied Jesus three times on the night of his death. Paul says he appeared to the twelve, and then he appeared to more than five hundred brothers and sisters at one time after he rose from the dead. Where is that in any of the four gospels? It’s not! Jesus leaves the tomb, and all of a sudden people are seeing him everywhere…

I don’t know if any of you have picked up this week’s issues of Time and Newsweek but, judging by their cover stories, what’s going on here at church this morning is big news. As we gather to celebrate the risen Lord, the question begging to be asked is, “where did Jesus go?” The gospel of Mark says remarkably little on this topic. The tomb is empty, and a messenger waits for those who gather to tell them that Jesus has gone on ahead of them. Later gospels began to add to the story, with visions of Jesus at the tomb and an ascension into heaven.

In its cover story, titled “Heaven Can’t Wait: Why Rethinking the Hereafter Could Make the World a Better Place,” Jon Meacham reports that among both religious conservatives and religious liberals a massive rethinking of the meaning of heaven has been underway for a while now. He writes,

In its cover story, titled “Heaven Can’t Wait: Why Rethinking the Hereafter Could Make the World a Better Place,” Jon Meacham reports that among both religious conservatives and religious liberals a massive rethinking of the meaning of heaven has been underway for a while now. He writes,

A more intimately connected heaven and earth is worth a deeper look. The debate doesn’t fit easily on the usual left-right, blue-red, liberal-conservative spectrum. That’s because each understanding is rooted explicitly in faith in the salvation history of Jesus. The divide isn’t about a secular ideal of service vs. a religiously infused vision of reality. It’s about whether believing Christians see earthly life as inextricably bound up with eternal life or as simply a prelude to a heavenly existence elsewhere.

He goes on,

For me, the scholarly redefinition of heaven as a manifestation of God’s love on earth has been illuminating, for it at once puts believers in closer proximity to the intent of the New Testament authors and should inspire the religious to open their arms more often than they point fingers. Heaven becomes, for now, the reality one creates in the service of the poor, the sick, the enslaved, the oppressed. It is not paradise in the sky but acts of selflessness and love that bring God’s sacred space and grace to a broken world suffused with tragedy until, in theological terms, the unknown hour when the world we struggle to piece together is made whole again. We could do worse than to think in such terms.

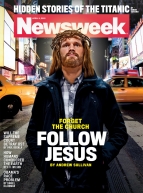

A little further down the magazine rack, occupying the cover of Newsweek, Andrew Sullivan’s story, “Forget the Church, Follow Jesus” takes up the coverage of what Christians are doing in church this morning. Rather than focusing on where Jesus went after leaving the tomb, Sullivan looks at where Christians are (and aren’t) going after they get out of bed on Sunday mornings. Namely, church. Christians, and increasingly those who don’t identify with any religious tradition, are fine with the idea of heaven as an earthly reality, they just don’t see that church has much to do with it. “Christianity itself,” he writes, “is in crisis.

A little further down the magazine rack, occupying the cover of Newsweek, Andrew Sullivan’s story, “Forget the Church, Follow Jesus” takes up the coverage of what Christians are doing in church this morning. Rather than focusing on where Jesus went after leaving the tomb, Sullivan looks at where Christians are (and aren’t) going after they get out of bed on Sunday mornings. Namely, church. Christians, and increasingly those who don’t identify with any religious tradition, are fine with the idea of heaven as an earthly reality, they just don’t see that church has much to do with it. “Christianity itself,” he writes, “is in crisis.

It seems no accident to me that so many Christians now embrace materialist self-help rather than ascetic self-denial — or that most Catholics, even regular church-goers, have turned out the hierarchy in embarrassment or disgust. Given this crisis, it is no surprise that the fastest-growing segment of belief among the young is atheism, which has leapt in popularity in the new millennium. Nor is it a shock that so many have turned away from organized Christianity and toward “spirituality,” co-opting or adapting the practices of meditation or yoga, or wandering as lapsed Catholics in an inquisitive spiritual desert. The thirst for God is still there. How could it not be, when the profoundest human questions — Why does the universe exist rather than nothing? How did humanity come to be on this remote blue speck of a planet? What happens after death? — remain as pressing and mysterious as they’ve always been? That’s why polls show a huge majority of Americans still believing in a Higher Power. But the need for new questioning — of Christian institutions as well as ideas and priorities — is as real as the crisis is deep.

Andrew Sullivan’s article has started a bit of a stir, and I suspect we’ll be hearing all sorts of retorts to his diagnosis that Christianity is in crisis. Diana Butler Bass, one of the best known and most published contemporary sociologists of religion (and author of the recently released Christianity after Religion: the End of Church and the Birth of a New Spiritual Awakening) has already filed her reply on the pages of the Huffington Post. In an article appropriately titled for today, “A Resurrected Christianity” she writes,

Andrew Sullivan’s article has started a bit of a stir, and I suspect we’ll be hearing all sorts of retorts to his diagnosis that Christianity is in crisis. Diana Butler Bass, one of the best known and most published contemporary sociologists of religion (and author of the recently released Christianity after Religion: the End of Church and the Birth of a New Spiritual Awakening) has already filed her reply on the pages of the Huffington Post. In an article appropriately titled for today, “A Resurrected Christianity” she writes,

Far too many churches are answering questions that few people are asking. This has left millions adrift, seeking answers that religious institutions have largely failed to grasp. But this may be changing. Around the edges of organized religion, …Christians have heard the questions and are trying to reform, reimagine, and reformulate their churches and traditions. They are birthing a heart-centered Christianity that is both spiritual and religious. They meet in homes, at coffeehouses, in bars — even in some congregations. They are lay and clergy, wise elders and idealistic hipsters. Some teach in colleges and seminaries. They even hold denominational positions. Not a few have been elected as bishops. The questions are rising up from the grassroots up — and, in some cases, the questions are reaching a transformational tipping point.

In ages past, beginning with the 17th century Enlightenment, Christianity has been asking the following set of questions, writes Bass:

- What do I believe? (What does my church say I should think about God?)

- How should I believe? (What are the rules my church asks me to follow?)

- Who am I? (What does it mean to be a faithful church member?)

“But,” she writes, “the questions have changed. Contemporary people care less about what to believe than how they might believe; less about rules for behavior than in what they should do with their lives; and less about church membership than in whose company they find themselves. The questions have become:

- How do I believe? (How do I understand faith that seems to conflict with science and pluralism?)

- What should I do? (How do my actions make a difference in the world?)

- Whose am I? (How do my relationships shape my self-understanding?)”

People of St. Luke’s, I hope you hear yourself in this emerging understanding of a resurrected Christianity. I certainly see you, wise elders and idealistic hipsters, located in these words. You are asking a new set of questions, you believe it is possible to be both spiritual and religious — and even that each can strengthen the other.

And, to those of you who are visiting with us today, I hope that you hear in these reports from the front lines of the emerging church signs that there is not only a past to this place, but a future. I hope you can sense that the people who gather in this sanctuary and so many other sanctuaries are not merely clinging on to remnants of a cherished past, but that they are “imaginative, passionate, faith-filled people… enacting a new-old faith.” They are a part of God’s future… a future we first caught sight of when the women went to the tomb expecting to find a dead body and were informed that God in Christ Jesus had already left that place to go on ahead of them.

A church built to get people to heaven loses sight of the plight of the earth. Unlike Christ, whose body it claims to be, the church has not always or often spoken for the rights of the widow, the orphan, the stranger. The hungry, the naked, the lost. The immigrant, the teenage mother, the street kid. Our religious institutions powered through the early part of the last century with the assumption that they spoke for everyone, even as they ignored those who differed from them in almost any way. They assumed that church, this big empty cavernous room, is where people would come to find God. But God is not here.

God continues to go where God’s people are. And if it happens to be the case that the number of people who do not use the name “Christian” has jumped from 8 to 15 percent in the last twenty years, then my guess is that God has gone ahead of us to Galilee, to the sea, to the lake, or the river. Wherever people are gathering to find community and draw strength from each other in order to face the trials of life and change the world.

God is at the sand volleyball courts on Lake Michigan, taking pleasure in the camaraderie of friends. God is at the car wash, working for tips. God is up all night with the twins. God is occupying Chicago and preparing for the upcoming NATO summit . God is welcoming another foster child into her home. God is relocating to a different city, starting a new job, making new friends. God is waiting for surgery to be scheduled. God is hoping to get through finals without losing her mind.

God is not here, because God has left the tomb to be part of the lives of living people. God, who cares for the living, not the dead, wants nothing more than to be a part of each moment of your life – whoever you are. God is not here, but you are.

I don’t know what the future of the church is, and on some level I don’t care. I grew up in the church, and when I was just a boy of 14 years old I told my family that I thought God wanted me to be a pastor. My dad reminded me that God’s wants something for each of us. We’re all called to be somebody in God’s world. We are all anointed, God’s chosen. After years of working with runaway and homeless youth, I came back to the church because I wanted the things I’d heard and experienced here, in a place like this, to become meaningful for all the people who aren’t here, in a place like this. So if we have to shut all these places down and find a totally new, totally transformed, totally resurrected way of living in order to embody the message of the living God, who is always going ahead of us leading us into the future – not behind us, holding us in the past – then that’s fine by me, because God is not here.

Hopefully though, what is here, what remains are the angels, those saints of God dressed in the white robes of their baptism, people ready to greet the visitor at the tomb with words of comfort and reassurance, “do not be alarmed… go, tell his disciples…you will see him, just as he told you.”

Maybe we can be those people, those angels, those guides. Maybe what we do here each Sunday, and throughout the week, is to fit people with the eyes of faith so that they can notice, name, recognize, rejoice in God when God is met ahead of us, out in the world.

Christ is Risen. Alleluia!

Christ is Risen Indeed. Alleluia!

One thought on “Sermon: Sunday, April 8, 2012: Resurrection of Our Lord — Easter Day”