Texts: Genesis 3:14-19; 4:8-16 + Psalm 139:7-12 + Romans 5:12-17 + Matthew 12:38-40

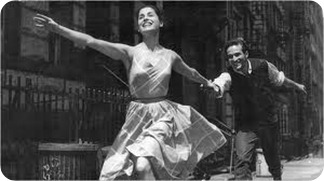

One of my favorite musicals of all time is West Side Story. I watch the 1961 movie adaptation every couple of years, and each time I’m caught off guard by how a story that begins with so much hope and romance can end up so sad and depressing. It’s epic in its tragedy. And, of course, it’s based on Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, so you know the story before you even watch. It’s archetypal.

One of my favorite musicals of all time is West Side Story. I watch the 1961 movie adaptation every couple of years, and each time I’m caught off guard by how a story that begins with so much hope and romance can end up so sad and depressing. It’s epic in its tragedy. And, of course, it’s based on Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, so you know the story before you even watch. It’s archetypal.

The same is true of Genesis, that book of the bible that begins with the two accounts of creation in which God makes earth and all its creatures and calls it all good. And not just the “good” that we might use at dinnertime in response to the question, “how was your day?” The Hebrew used in Genesis is rich, sensual, evocative language that gets repeated in the Song of Solomon. Eden is a garden rich and fertile and intensely pleasurable to God and for all of creation. It is a place of so much hope and romance…and so quickly it begins to fall apart.

As we noted last week, the book of Genesis spins myths about creation that convey a memory of the deep inter-relatedness of all that God made. The earth and sea and sky, and all their creatures are related to one another, and to humankind – which God tasks with tending to the care of creation. We are invited to name the animals the way we might name our own children, because they are kin to us, and all of us children of God.

Then the rupture begins. A tree of knowledge. Forbidden fruit. The curse pronounced on Adam and Even, that both will endure forced labor – she in giving birth and he in working the land. But listen again to the final verses of Genesis 3, paying special attention to the relationship between humanity and the land:

Cursed is the ground because of you; in toil you shall eat of it all the days of your life; thorns and thistles it shall bring forth for you; and you shall eat the plants of the field. By the sweat of your face you shall eat bread until you return to the ground, for out of it you were taken; you are dust, and to dust you shall return.

I don’t know about you, but when I think about how the story of the garden of Eden has been told and taught to me, it always felt like the moral of the story was that Adam and Eve were being punished for disobeying God’s rules and eating the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. I’ve heard plenty of speculation about what that fruit symbolizes, and questions about why humanity was commanded to avoid knowledge, which seems like a good thing. But there was never really much discussion about what “the fall” meant for the land.

“Cursed is the ground because of you… until you return to the ground, for out of it you were taken; you are dust, and to dust you shall return.”

God’s message to the first people seems clear: you have separated yourself from the land in ways that are a curse to both you and the land, and will remain so until you remember that you and the land are one.

Although Genesis is presented as the first book of the bible, modern biblical scholarship assumes that it is a product of the period of time when the people of Israel were in exile. It is profoundly retrospective literature. The kingdom of David and Solomon had divided on itself and been conquered from outside, and all the hope and possibility of the people who had entered the promised land and taken dominion seemed dashed. You can almost hear the teachers and story-tellers responding to the people’s question, “what went wrong?”

In response to that fundamental question, Hebrew scriptures don’t make excuses, or point the finger at their enemies and shirk from their part in the whole mess. Instead, with the words of Psalm 139 on their lips, “where can I flee from your presence?” they took a hard look at their predicament and told an origin story in which humanity’s misery began as it left the sustainable lifestyle of the earlier hunter/gatherer tribes and moved into the world of agriculture and the civilizations to which it gave rise.

So Adam and Eve give birth to Cain the farmer and Abel the shepherd. Genesis says that “In the course of time Cain brought to the Lord an offering of the fruit of the ground, and Abel for his part brought of the firstlings of his flock, their fat portions. And the Lord had regard for Abel and his offering, but for Cain and his offering he had no regard.” (Gen. 4:3-5) So Cain lures Abel into the field and kills him, and for the second time in twice as many chapters, the ground is cursed by human action as God laments,

“What have you done? Listen; your brother’s blood is crying out to me from the ground! And now you are cursed from the ground, which has opened its mouth to receive your brother’s blood from your hand. When you till the ground, it will no longer yield to you its strength; you will be a fugitive and a wanderer on the earth.” (Gen 4:10-12)

The rift between humankind and the earth is played out in an episode of family violence, as humanity continued to distance itself from land, sea, sky and all their creatures, our kin.

I won’t go into all the details here, but there is wonderful biblical scholarship that looks at these stories from Genesis, and the ones that follow, as ancient reflections on the rise of civilization. The movement from tribal life to more fixed agricultural economies allowed for the rise of settlements, then cities, then kingdoms. This meant the need for warriors to guard the wealth that accumulated in such places, then armies to conquer and acquire the wealth of others.

But these scriptures are millennia old, reflecting on a transition that humankind made millennia before that. What relevance could their observations have for us today? What does the theological imagination of a nation of people captive to war, alienated from their homeland, economically dependent on foreign nations, and longing for a return to better days have to do with us, here, in the United States, a decade into the longest war in our nation’s history – having surpassed the Vietnam War almost 16 months ago?

Our remarkably short gospel reading this morning reveals Jesus in passionate debate with the religious establishment during the time of the Roman occupation. Jesus has taken John the Baptist’s message of repentance and has cracked it open for people from every tribe and nation and empire – challenging the established order and its inherent violence. The scribes and Pharisees can’t or won’t acknowledge that what Jesus is preaching is the same message the prophets of Israel had always brought when faith got too cozy with empire, so they ask for a sign to prove the validity of what he’s saying.

Instead Jesus offers the sign of Jonah, who spent three days in the belly of the whale. Remember Jonah? He was a prophet of God sent to call Ninevah to repentance. Jesus evokes the memory of Jonah, and the early church told this story, as a way of claiming that mantle of prophetic critique against the powers of empire… but also as a sign that, as with Ninevah, it was not too late to repent.

By faith, we have to hope that the same is true for us. Our alienation from the very earth out of which we are created has led not only to disastrous consequences for the soil, it has been reflected in and amplified by our warring with our neighbors. Afghanistan, once covered by forests, now has less than 2% forest cover as a result of a decade of bombing and refugees scavenging for firewood. The skies above Afghanistan, once one of the world’s major migratory pathways, has lost almost 85% of the birds which once flew on its winds. The pollution left behind by explosives has proven carcinogenic and is shown to cause thyroid damage. The land, littered with land mines, no longer sustains life.

Truly: “Cursed is the ground because of [us]… until [we] return to the ground, for out of it [we] were taken; [we] are dust, and to dust [we] shall return.” Our violence toward one another poisons the land, and because we are made of earth and return to the earth, everything we do to the land eventually returns to haunt us.

In his commentary on the passages for this second Sunday in the Season of Creation, theologian Ched Myers, who has written extensively on restorative justice and peacemaking, joins the apostle Paul in claiming for Jesus the role of the one who reverses the dissolution of Adam and Eve and their sons, calling Jesus “God’s ultimate countermeasure to the fall.”

Jesus is baptized by John in the wild waters of the Jordan, far from the domesticated ritual baths of Judean cities (3:13-17). The Nazarene prepares for his ministry with a wilderness vision-quest to find out where his people went wrong (4:1-11). His inaugural sermon proclaims the incompatibility of God with the mammon system (6:24), and declares that the smallest wildflower has more intrinsic value from the divine point of view than the grandest civilizational pretensions of Israel’s greatest king, Solomon (6:28f). Jesus symbolizes the ‘retribalization’ of Israel in his naming of the twelve disciples (10:1-4), and directly challenges imperial cities to repent (11:20-24). He enacts the Jubilee principle of the right of the poor to the edge of every field (12:1-8), and communicates with illiterate peasants through stories about the land: ‘A sower went out to sow…’ (13:3). His seed parables envision the kingdom of God not as some otherworldly place and time, but as the reclamation of the very soil upon which Palestinian serfs toil (13:24-32).

Jesus Christ, the sign of God’s solidarity with the suffering of God’s creation, God’s reconciliation for humanity and God’s redemption for the earth, lies deep in the heart of the ground for Jonah’s three days, then rises to proclaim that God’s story does not end in tragedy, but in triumph.

For us the challenge is to take the epic and the archetypal and to apply it to our everyday lives. It is the challenge to think globally and act locally. How do we share the land the surrounds our own homes, our church home? How is violence carried out on the streets of Chicago tied to the violence done to the land beneath our feet and the waters that supply our homes? What sickness are we spreading on the land and reabsorbing into our skin? Where does the oil pulled from the ground to fuel our cars end up, and to what effect? How do we heal the earth and its inhabitants while we continue to carry out a war against our neighbors around the globe?

Genesis, like West Side Story, like Romeo and Juliet, is epic and archetypal in its tragedies. The Season of Creation has a story arc as well, beginning with the forests of creation and then our alienation from the land. Now the story begins to pivot toward hope. Next week we turn to the wilderness as the place of God’s passion and presence, and the following week we remember the rivers as the waters of new creation and we celebrate the baptism of two of our children, Johnnie and Rachyl Lindquist, along with the First Communion they will share with their Sunday School classmates on that day.

As we move from the word to the meal this morning, let’s pray for a deeper communion with the land and all who live upon it. As we consume this bread and this wine, let’s pray for the soil out of which the grain to make our bread and the grapes to make our wine were grown. Let this meal remind us that what we do to the land, we do to ourselves. As we take each step on our way to the communion rail, let’s pray that God will help us take one step closer to home, the good earth of the garden from which we came and to which we are returning.

Amen.

2 thoughts on “Sermon: Sunday, September 18, 2011: Second Sunday in the Season of Creation”