Texts: Isaiah 65:17-25 • Psalm 118:1-2, 14-24 • Acts 10:34-43 • Luke 24:1-12

Forty-two years ago today, Chicago exploded.

I was still five years away from being born, so if you’re my age or younger then you learned about this explosion the same way I did, through history books. But some of you were here to see it happen. Some of you were my age, or just a little younger, at the time of the 1968 riots.

April 4, 1968 the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee where he was speaking in support of African-American sanitation workers who were demanding equal pay and equal working conditions. He had just delivered one of the most famous speeches of his career, in which he prophesied,

We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn’t matter with me now. Because I’ve been to the mountaintop. And I don’t mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land! And so I’m happy tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord!

The next day he was shot and killed, and the nation exploded in riots of grief that gave rise to anger and destruction of property and lives, as mourning communities clashed with police officers in the streets of Chicago, Baltimore, Kansas City, Louisville and Washington, DC.

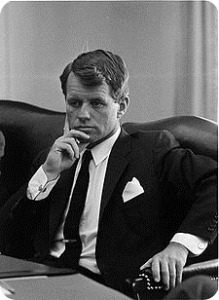

At that time, New York Senator Robert F. Kennedy was running for president and had been campaigning in Indiana. Near the end of the day, Kennedy received news of King’s death. He was scheduled to speak in Indianapolis that night, and as he arrived at the rally, the Chief of Police stopped him to tell him that it was too dangerous to bring up the subject of King’s assassination, and that he would not be able to protect him if a riot broke out. Kennedy decided to take his chances, and he spoke to the crowd assembled there for just under five minutes. He said,

At that time, New York Senator Robert F. Kennedy was running for president and had been campaigning in Indiana. Near the end of the day, Kennedy received news of King’s death. He was scheduled to speak in Indianapolis that night, and as he arrived at the rally, the Chief of Police stopped him to tell him that it was too dangerous to bring up the subject of King’s assassination, and that he would not be able to protect him if a riot broke out. Kennedy decided to take his chances, and he spoke to the crowd assembled there for just under five minutes. He said,

What we need in the United States is not division; what we need in the United States is not hatred; what we need in the United States is not violence and lawlessness, but is love, and wisdom, and compassion toward one another, and a feeling of justice toward those who still suffer within our country, whether they be white or whether they be black…

We can do well in this country. We will have difficult times. We’ve had difficult times in the past, but we – and we will have difficult times in the future. It is not the end of violence, it is not the end of lawlessness; and it’s not the end of disorder.

But the vast majority of white people and the vast majority of black people in this country want to live together, want to improve the quality of our life, and want justice for all human beings that abide in our land.

And let’s dedicate ourselves to what the Greeks wrote so many years ago: to tame the savageness of man and make gentle the life of this world. Let us dedicate ourselves to that, and say a prayer for our country and our people.

And two months later, Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated.

It was a year of incredible grief and violence and chaos and confusion in this land. The hope that King and Kennedy had inspired in our nation was the hope that our future would not be defined by our past. It was hope that out of the ashes of a past scarred by slavery and consumed by war, there could peace in the United States and peace abroad, and that the people of our nation, and all the peoples of the world could find a way forward that recognized our mutual interdependence. When they were killed, we wondered if those dreams had died as well.

That despair, those depths, are what the women who came to the tomb were feeling. They had followed Jesus throughout his ministry. They had heard him on the campaign trail, stumping for God’s politics – a politics of unity and provision. An agenda that time and time again showed Jesus handing out healthcare for free, as he laid hands on lepers and blind people, casting out demons and curing those who had been bled dry for years. A movement that called for immigration reform, as Jesus crossed back and forth over the southern border between Israel and Samaria again and again, entering into conversations of respect with people regarded as dirty, uneducated, religiously inferior foreigners, calling attention to their inherent dignity with stories like the Good Samaritan. They had marched with him into Jerusalem, where he spoke with power and authority to the leaders of the nation of Israel, and even the representatives of Rome.

He refused to back down. He refused to be silent. Like the King who told his followers in Memphis, “Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will,” this Jesus had looked at the future that awaited him and prayed, “Father, if you are willing, remove this cup from me; yet, not my will but yours be done.” And there in Jerusalem, he was assassinated.

And the women wondered if his dream had died, and their hopes for the future with him. But when they arrived they found the stone rolled away from the tomb, and when they went in they did not find the body. And while they were standing there, perplexed and confused, two men came and stood among them and asked,

Why do you look for the living among the dead? He is not here, but has risen. Remember how he told you, while he was still in Galilee, that the Son of Man must be handed over to sinners, and be crucified, and on the third day rise again?

And then these women seem to get the point, and they run to the rest of Jesus’ followers and tell them what they had heard, but the scriptures say that the men regarded these women’s words as “an idle tale.”

An idle tale. A silly story. Nonsense. Had they forgotten already the power of a story? Had they forgotten already that, while he was alive, Jesus taught mainly by story? Apparently so, but not all of them.

Peter gets up and runs to the tomb, and the story spreads that the tomb was empty, that Jesus had risen. Risen like a loaf of bread, full of yeast and rising as it bakes in the fire. Rising, but where?

Jesus rises into each of us. Peter, who hears the women’s story, and decides to regard it as something other than nonsense, carries the story out into the world, so that in the second lesson for this morning we hear him preaching Jesus’ message, picking up where he’d left off on the campaign trail. He says,

I truly understand that God shows no partiality, but in every nation anyone who fears God and does what is ri

ght is acceptable to God.

It is the seed that germinates and grows into RFK’s confident hope that

the vast majority of [people] in this country want to live together, want to improve the quality of our life, and want justice for all human beings that abide in our land.

The messenger may die, but the message rises. The message is alive, and it cannot be killed. The message cannot die. Why do we look for the living among the dead? It is risen!

There is an incredible scene at the end of the movie Spartacus, the 1960 movie by Stanley Kubrick with Kirk Douglass and Tony Curtis. Spartacus has led a revolt of slaves against the Roman empire, attempting to bring an end to their slavery once and for all. The revolt fails, but the revolution takes root in the heart of the people in a way that cannot be killed. Cornered and defeated by the Roman legion, the rebels are addressed by a Commander of the Roman army, who tries to make a deal with them in order to finally capture and make an example out of their leader. He says,

I bring a message from your master…by command of his most merciful Excellency, your lives are to be spared. Slaves you were, and slaves you remain. But the terrible penalty of crucifixion has been set aside on the single condition that you identify the body or the living person of the slave called Spartacus.

Slaves you were, and slaves you remain. But you can have your life back, if you are just willing to accept slavery as your permanent condition, and if you will give up the idea of liberation that Spartacus has come to represent. That is the empire’s offer.

And as the real Spartacus rises to his feet to give himself up, the entire group of rebels rise as well, each of them declaring, “I am Spartacus!” The messenger may die, but the message rises. The message is alive, and it cannot be killed. The message cannot die. Why do we look for the living among the dead? It is risen!

That scene from Spartacus has been imitated in dozens of movies and books and television shows, some serious others humorous, one of my favorites is at the end of Spike Lee’s movie about the life of Malcolm X. Once again, the messenger is killed, assassinated by rival religious and political operatives, but the movie ends with images of other black liberation movements around the world, from Harlem to Soweto, as Ossie Davis delivers a voice over,

In honoring him, we honor the best in ourselves…let his going from us serve only to bring us together now. Consigning these mortal remains to earth, the common mother of all, secure in the knowledge that what we place in the earth is no more now a man, but a seed, which after the winter of our discontent will come forth again to meet us, and we shall know him then for what he was and is – a Prince. Our own black, shining prince, who didn’t hesitate to die, because he loved us so.

Then the movie cuts to a classroom filled with children no more than ten years old, and their teacher, who tells the children, “we celebrate Malcolm X’s birthday because he was a great Afro-American. And Malcolm X is you, all of you, and you are Malcolm X.” Then, like the slaves in revolt against the Roman Empire, rising to their feet to claim the name of Spartacus, these little children rise from their little desks and cry out, “I’m Malcolm X!” The messenger may die, but the message rises. The message is alive, and it cannot be killed. The message cannot die. Why do we look for the living among the dead? It is risen!

Two thousand years ago, the world exploded. None of us here in this room were alive to see it, so we have learned what we can from the stories of those who came before us. And we gather this Easter, as Christians have gathered for two thousand years, to stand eye to eye with all the forces of this world that try to swindle us out of our birthright as children of God; who tell us that slaves we were and slaves we remain, but that we can keep our lives as long as we’re willing to settle for slavery as a permanent condition and give up on this idea of freedom – freedom from false distinctions that separate us from our brothers and sisters – give up on the name by which we have come to know and cherish the freedom that has been ours since the day we were born in baptismal waters. Give up on the name “Jesus.”

And our reply today, as it has been ever since the women went to look for the body of Christ in the tomb, remains, “I am the body of Christ!” We are the body of Christ! God’s work, our hands. The messenger may die, but the message rises. The message is alive, and it cannot be killed. The message cannot die. Why look for the living among the dead? We are risen!

P Alleluia! Christ is risen!

C Christ is risen indeed. Alleluia!